1. Archeology and Ancient Taiwan

Chen Yu-bei1

1.1. Taiwan’s past

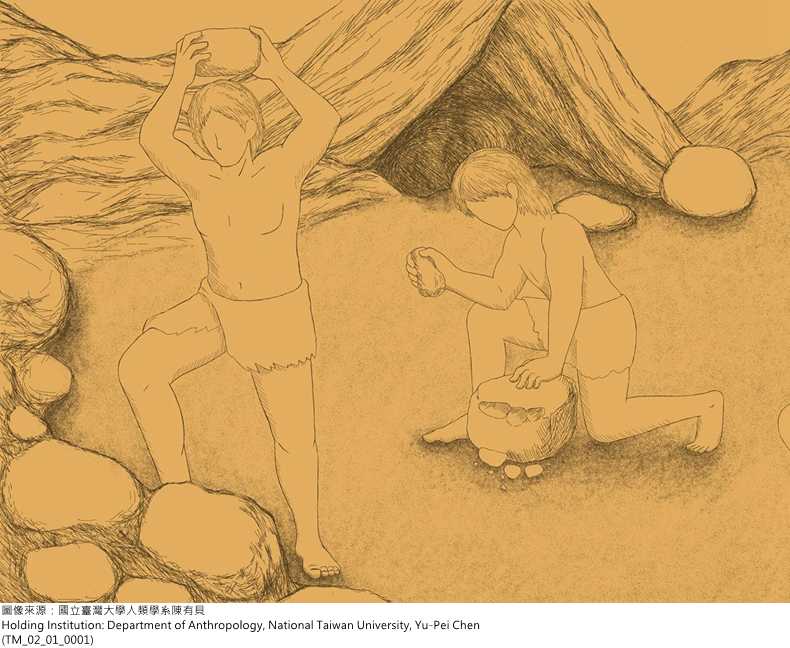

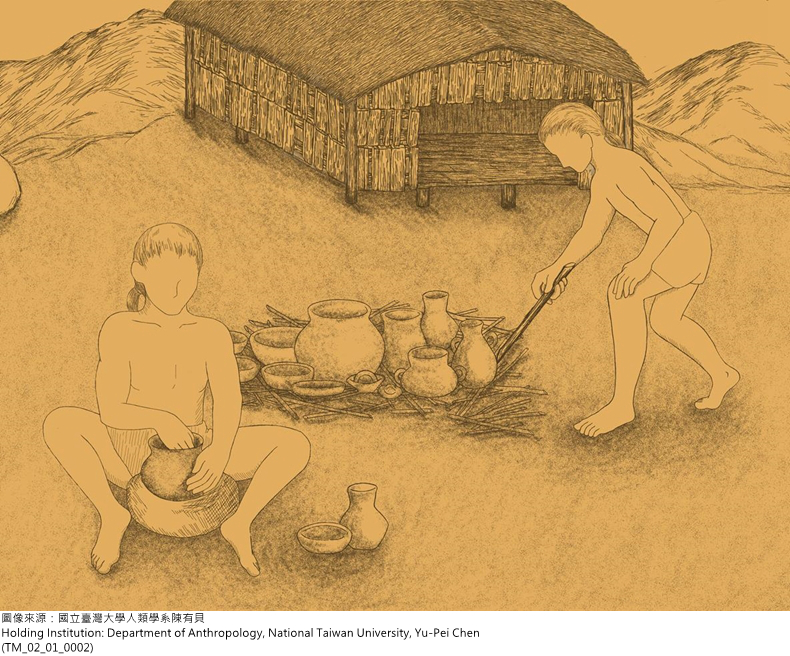

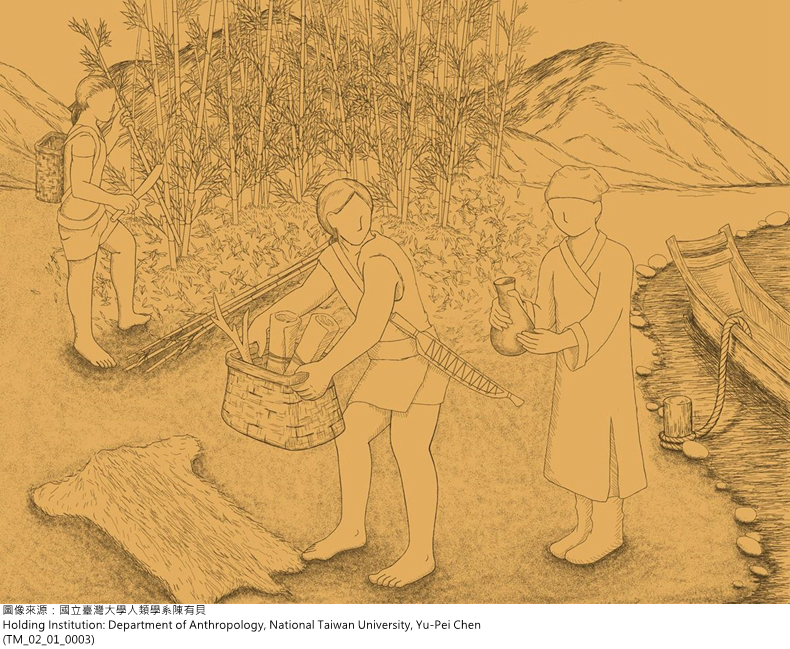

Although the island of Taiwan formed millions of years ago, people did not begin to arrive until about 30,000 years ago. Researchers divide Taiwan’s history into the Paleolithic Period, Neolithic Period, Iron Age, and historical period, according to the stage of cultural development reached by the island’s population. The people of Paleolithic Taiwan mainly used chipped stone tools; agricultural practices appeared in the Neolithic Period, as did techniques for making polished stone tools and ceramics; and in the Iron Age people began to use iron tools, which further accelerated the complex development of culture. These three eras are collectively known as Taiwan’s prehistoric era, due to the absence of any written records.

Image TM_02_01_0001 Impression of life in the Paleolithic

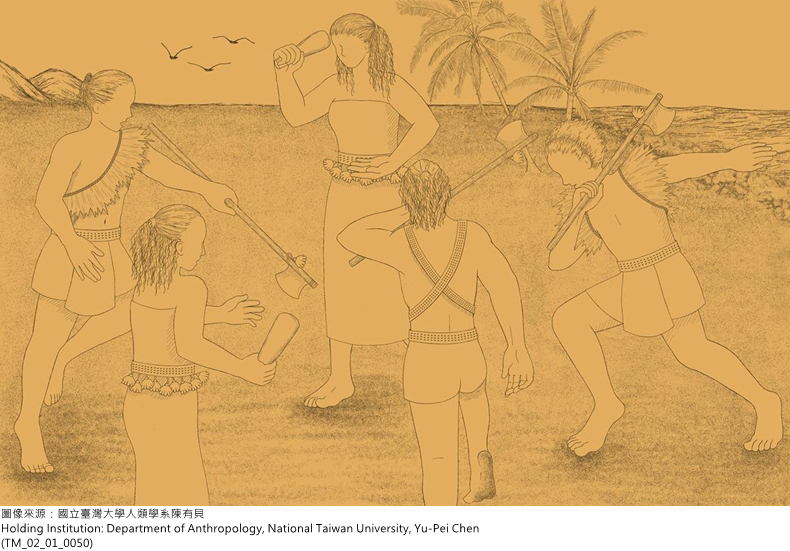

Image TM_02_01_0002 Impression of life in the Neolithic

Image TM_02_01_0003 Impression of life in the Iron Age

The emergence of written language marks the beginning of the historical era. There are much clearer records of the societies of this period, but because the majority of Taiwan’s historical documents were not written by indigenous Taiwanese people, these records are inevitably somewhat biased against them in both perspective and content. Researchers therefore must be more objective when interpreting the historical record, so that they are able to cut through the layers of misleading information, and come closer to the reality of people’s lives in those times.

1.2. Archeology in Taiwan

Archeology and history are the two main branches of knowledge we use when researching the past. Generally speaking, we can only guess at what the lives of those people living in the prehistoric era may have been like based on archeological relics and their interpretations. For the historical era, for which we do have written records, we can compare the historical and archeological records, contextualize historical events and verify their historicity. Documents relating to the early historical period in particular are often not completely reliable, and in these circumstances archeology becomes comparatively important.

Archeology as an academic discipline in Taiwan dates back to the end of the nineteenth century. During this early period, Japanese scholars conducted all archeological surveys and research in Taiwan. Following the Second World War and departure of the Japanese, Taiwanese archeology was instead led by Chinese scholars who had relocated to Taiwan from the mainland, and since then has integrated the theories and developments of world archeology. The rich variety of ecologies and cultural backgrounds present on the island provide ideal materials for archeological research, earning Taiwan a reputation as an ‘archeological laboratory’.

1.3. Archeological methods

Archeology uses the various remains left behind by people of the past to research ancient cultures and societies. In other words, although it is objects that are analyzed, the goal is to explain the different phenomena present in these human communities.

Wherever humans are active, they leave behind all kinds of traces of their activities. Through excavation, archeologists are able to uncover these clues, and then apply various methods of research and analysis to recover ancient culture, or offer better interpretations of it.

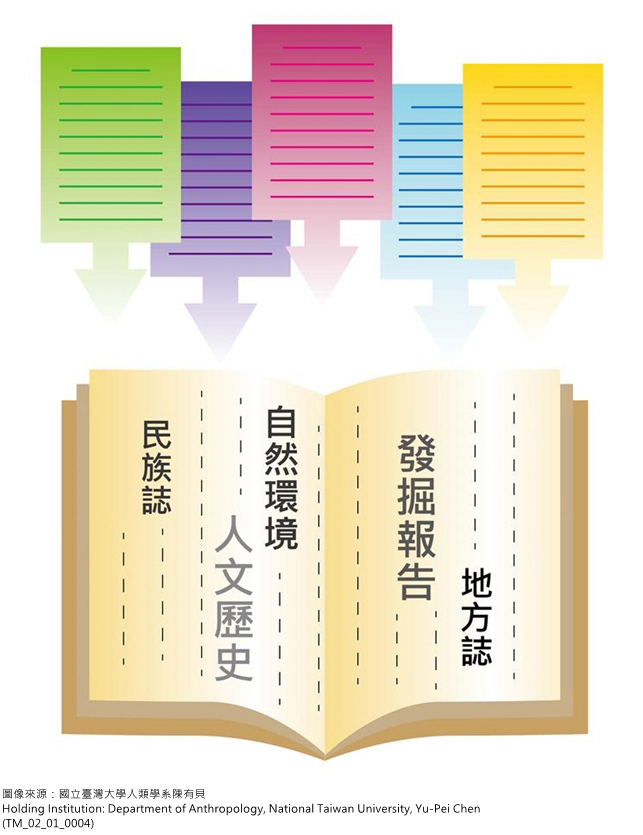

In specific terms, archeological work consists of a series of tasks. It begins with the emergence of a research question; then data is gathered, field surveys conducted, and excavations carried out. Finds are then sorted, the data analyzed, and a report is written, which provides scholars with a variety of fundamental data to research.

Image TM_02_01_0004 Data gathering

Image TM_02_01_0005 On-site archeological work: drilling

Image TM_02_01_0006 On-site excavation: opening a test pit

Image TM_02_01_0007 On-site excavation: photographing

Image TM_02_01_0008 On-site excavation: surveying and mapping

Image TM_02_01_0009 On-site excavation: sketching phenomena

Image TM_02_01_0010 Sorting at the lab: washing finds

Image TM_02_01_0011 Sorting at the lab: recording finds

1.4. The future of Taiwanese archeology

Archeology as a discipline has developed in Taiwan over the course of more than a century. The tireless dedication to research of each generation of scholars has already achieved a great deal; but as archeology advances ever more rapidly with each passing generation, in the future we can expect further developments that provide us with an even broader range of knowledge.

One of the most remarkable changes during the development of archeology has been the application of scientific techniques. Today, we can analyze the constituent elements of a relic and be able to infer where it was originally produced, or ascertain whether a piece of land was once used for agriculture by analyzing particles in the soil, such as silica bodies. DNA analysis may even be utilized to get a picture of the kinds of organisms present, or to establish genetic relationships between ethnic groups.

Archeology today makes active use of various technologies, in the hope that they will help answer more of the questions we have about humankind’s past. This will also be the future of Taiwanese archeology.

2. Paleolithic Taiwan

2.1. The first Taiwanese

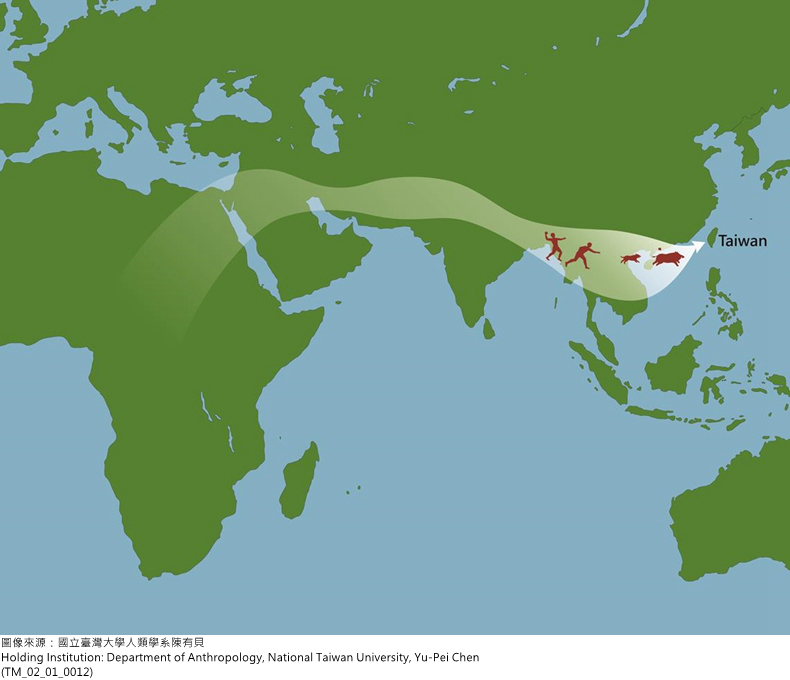

According to the most recent research, the most direct ancestor of modern human beings was not, as was previously thought, Peking Man or Neanderthal Man, but a new group of humans that evolved in Africa about 200,000 years ago. An estimated 50,000 to 60,000 years ago, a small group of these humans arrived in mainland East Asia, possibly reaching Taiwan a short time later.

Image TM_02_01_0012 Possible migration path taken by early humans

According to existing archeological surveys, the most ancient archeological discovery on the island of Taiwan was the Baxian Caves (八仙洞) site in Taitung County. The main evidence of ancient human activity were traces unearthed from the ancient layers of the site, which were then carbon dated to approximately 30,000 years ago.

Image TM_02_01_0013 The Baxian Caves site: topography of the sea shore

Image TM_02_01_0014 The Baxian Caves site: cave in the cliff side

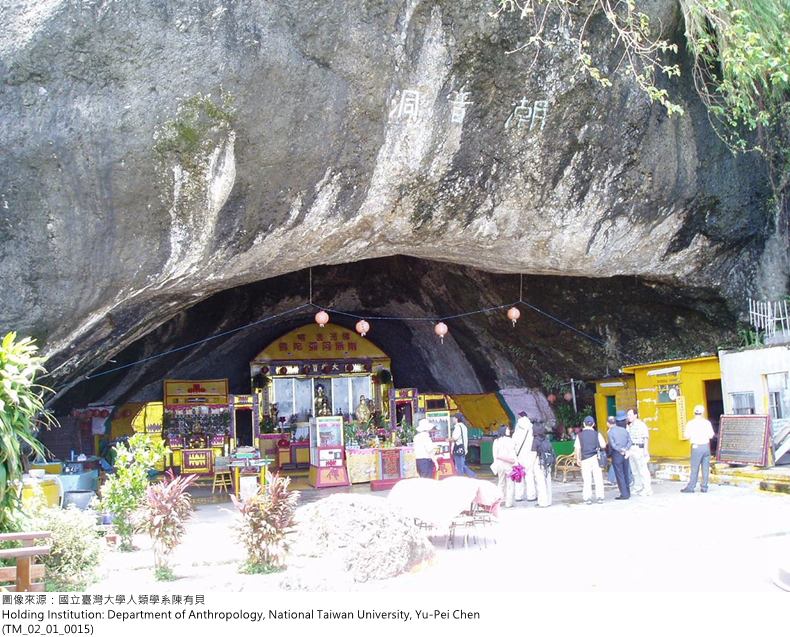

Image TM_02_01_0015 The Baxian Caves site: modern use of the caves

2.2. Where did they come from?

There are currently two explanations for the origins of the first Taiwanese. The first argues that during the last ice age at the end of the Pleistocene era, sea levels had fallen low enough for a land bridge to appear, connecting Taiwan with the coast of southeastern China. Humans crossed this land bridge into Taiwan in pursuit of animals they were hunting. The second possible explanation is that sea-fishing communities fishing off the Maritime Southeast Asian coast were either carried by sea currents to Taiwan, or followed shoals of fish there. If the first explanation is correct, then the first Taiwanese likely lived on the west coast; if the second is correct, then they most likely first appeared at Taiwan’s southern tip or somewhere on the east coast.

Image TM_02_01_0016 Case 1: The first Taiwanese originated from somewhere on the southeastern coast of mainland China. Base map adapted from Chen Wenshan (2016), “Changes in Taiwan’s Coastline since the last glacial maximum.” https://www.natgeomedia.com/news/external/44459

Image TM_02_01_0017 Case 2: They arrived from Maritime Southeast Asia.

Let’s examine the archeological evidence for the above hypotheses. Since the 1970s, the majority of scholars in the Taiwanese archeology community had no doubts about the existence of Tso-chen Man, a fossil human skeleton collected near Cailiao River in Tainan’s Zuozhen District. It was initially dated to between 20,000 and 30,000 years old, but when archeologists carbon-14 dated the assemblage of bones again in 2014-15, yielding an age of just 3,000 years, this posed a serious challenge to past understanding. Meanwhile, research on the Baxian Caves site also revealed human activity dating back at least 30,000 years. Moreover, after comparative research on several objects found at Baxian Caves site and at sites in Southeast Asia, the theory that the earliest groups to arrive in Taiwan originated from Southeast Asian coastline was gradually taken more seriously.

2.3. Hunters or fishermen?

If it is true that Taiwan’s earliest inhabitants crossed a land bridge from southeastern China to Taiwan, then it is likely they were mainly hunters; and if they made the crossing from the seas of Southeast Asia to Taiwan in boats, they were probably fishermen who mainly depended on sea fishing. It is of course possible that in reality there were both hunters and fisherman among the early Taiwanese, but this awaits further research.

Among the archeological finds from Baxian Caves, you often see rough-edged chipped stone tools, possibly used for hunting or crafting tools out of wood and bone. Another type of find is crafted from bone and known as an inverted T-shape fishing hook. These stick-shaped hooks are three to five centimeters long, sharpened at both ends, and often have a notch cut into the center. To use the hook, a line was tightly attached to the notch, and the outside covered in bait. When a fish took the bait, the line was tugged upwards, causing the hook to catch in the fish’s throat or mouth, and the fish was pulled in.

Image TM_02_01_0018 The inverted T-shape fishing hook and its use

Among the animal remains unearthed at the Baxian Cave site were a number of bones from large species of fish. It is not improbable that these fish were caught using the above method. Overall, the evidence seems to show that ocean resources were undoubtedly an extremely important component of the livelihood of Taiwan’s first inhabitants.

Taiwan’s earliest inhabitants chose to live in mountain caves. Just a few simple tools were enough to meet their needs and enable them to survive in much the same way for a very long period.

The majority of their tools were made of stone using striking methods. These can be divided into three types. The first type are stone core tools known as “choppers.” To make a chopper, an ellipsoid-shaped stone that could be comfortably held in the hand was chosen. Successive chips were then made on one face of the stone to create a rough edge. The heaviness of the stone made it useful for relatively strenuous work, such chopping, smashing, or pounding. Choppers could be used as weapons, hunting tools, or general tools. The second type of stone tool are chipped stone or flake tools. These were made from the pieces of stone obtained during the process of chipping a stone core tool, and were used mainly for relatively intricate and light tasks such as scraping, peeling, cutting, and severing. The third type are small, varyingly shaped stone tools made from quartz materials. These tools were usually pointed at one end, and perhaps used for piercing or drilling holes.

Image TM_02_01_0019 Chopping tools: Stone core tools

Image TM_02_01_0020 Stone flake tools

Image TM_02_01_0021 Irregularly shaped small stone tools: a pointed tool

Each of the above types of tool had different uses. Together with a variety of wood and bone tools, these were important tools that people used in their everyday lives.

2.5. Taiwan’s Paleolithic sites

At present, the best known Paleolithic site in Taiwan is at the Baxian Caves in Changbin Township, Taitung City. The Baxian Caves are a group of several dozen caves carved into a steep cliff face overlooking the sea. The caves were created sometime in the distant past by millennia of constant pounding of the waves against the cliff, when the sea level was much higher up the cliff. Later the land uplifted, exposing the caves. Humans arrived here 30,000 years ago and chose to live in the caves, which remained occupied by Paleolithic groups up until about 5,000 years ago. In light of the great significance of this site in the research of prehistoric Taiwan, in 2006 it was designated a National Archeological Site by the government.

Are there any other Paleolithic sites in Taiwan? There are some, and in theory there should be others. Lying just over 50 km south of Baxian Caves are the Xiaoma Sea Caves and Xiaoma Limestone Cave. Like the Baxian Caves site, the former site is a row of sea caves eroded into of the foot of a cliff. Besides the 5,000 year old Paleolithic objects unearthed here were human remains of the same age, making them to date the oldest known human skeletal remains to be unearthed in Taiwan. The latter is a 20-meter deep limestone cave with a narrow entrance, in which it seems there was special activity in ancient times.

Image TM_02_01_0022 The Xiaoma Sea Caves site

Image TM_02_01_0022 The Xiaoma Sea Caves site

Paleolithic artifacts have also been unearthed at the Eluanbi No. 2 site at the southern tip of Taiwan. This is a site of ancient habitation constructed from uplifted coral reef limestone, situated not far from the sea. It is thought that a community lived in the shade of the rocky cliff, eating large quantities of fish and shellfish caught on the coral reef. The archeological excavation here unearthed finds that included large quantities of the shells of consumed green snails, and moreover they were all large specimens. You can just imagine the people of those times gathering fish and shellfish here.

Image TM_02_01_0024 Shady cliff at the Eluanbi No.2 site

2.6. The possibility of finding other Paleolithic sites in Taiwan

Besides the extensive finds made at the Baxian Caves, Xiaoma Sea Caves, Xiaoma Limestone Cave, and Eluanbi No. 2 sites, there have also been occasional reports of Paleolithic finds in several areas. However further investigation of these is often constrained by environmental conservation concerns, and so the stratum and date of these findings still awaits more rigorous confirmation. This does not mean that there will be no further discoveries, and neither can the possibility of discovering even earlier people be excluded.

In theory, Taiwan’s first inhabitants could have originated in Southern China or Maritime Southeast Asia. The earliest site yet discovered in Southern China dates to about 200,000 years ago, and there have been even older sites found in the latter region. This means that it is certainly possible that people lived in Taiwan earlier than 30,000 years ago2. The problem lies in how to find proof for either hypothesis.

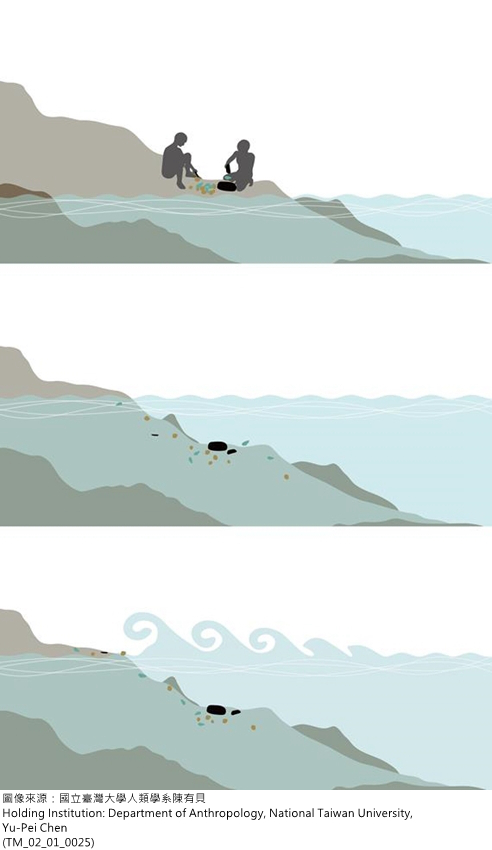

Xiagukeng is a very famous site situated on Taiwan’s north coast near the mouth of the Danshui River. The site is famous for the many prehistoric objects that can be found there, which even include apparently Paleolithic stone tools. However several surveys and excavations have failed to locate where these finds were originally deposited. It is possible that the site is already underwater, and that the finds were washed ashore3. In other words, the site is now on the sea floor. This is a very reasonable hypothesis when you consider that Taiwan’s first inhabitants lived on the sea shore. Sea levels later rose, submerging early sites, and this would mean that unfortunately a portion of west coast Paleolithic sites can only be reached by diving.

Image TM_02_01_0025 Possible process of Paleolithic site formation on Taiwan’s west coast.

As for the sea caves on the east coast, the considerable uplift experienced by this area of land tells us that the higher up the cliff the cave is, the earlier it was formed, and the stronger the possibility that traces of early human activity may be found there. Alternatively, the mountains of southern Taiwan, such as in the areas around Kaohsiung and Pingtung, contain significant areas of limestone terrain. This kind of environment is most suited to the long term preservation of organic objects, and so there is a greatly increased chance of finding ancient human remains there. If you aspire to finding Taiwan’s earliest humans, then you could do worse than start looking in these areas and environments!

3. The Neolithic Period

3.1. The second migration to the island of Taiwan

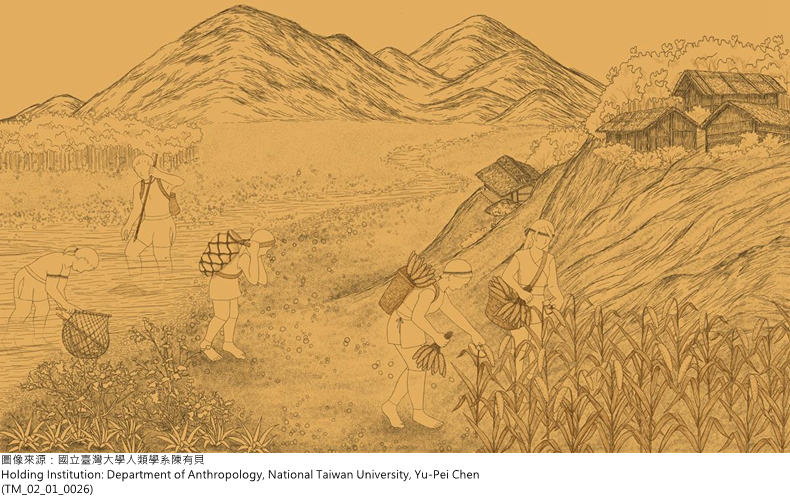

The first humans to migrate to Taiwan were Paleolithic peoples. The second major migration was undertaken by groups of Neolithic people from the southern East Asian mainland. Research has found that about 6,500 years ago a succession of new groups of people began moving to Taiwan. At that time sea levels were comparatively higher than previously, and so Taiwan was completely cut off from the mainland. For this reason we can say with some certainty that these people made the crossing by boat. After their arrival, they immediately developed a way of life adapted to living on an island. Archeologists refer to this way of life as the Dapenkeng Culture; several linguists and ethnologists conjecture that the language spoken by the Dapenkeng Culture was the common ancestor of the Austronesian languages4.

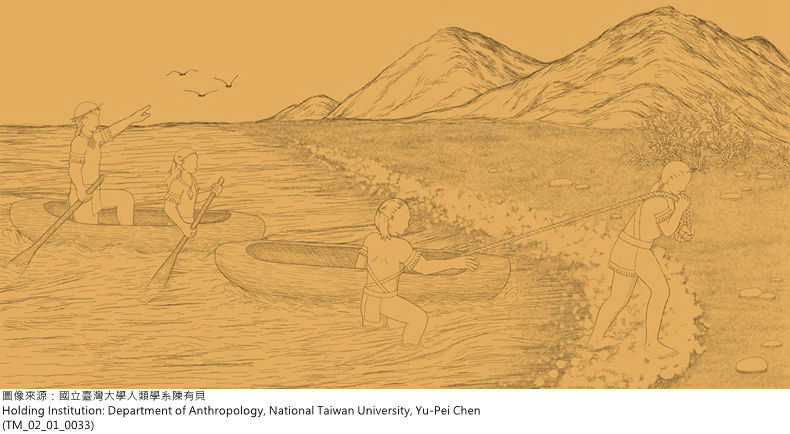

Image TM_02_01_0026 Impression of Austronesian peoples crossing to Taiwan by boat.

3.2. The Dapenkeng site

The name Dapenkeng originally referred to a place in the Bali District of New Taipei, situated near the mouth of the Danshui River. In the 1950s, an ancient site was discovered on a nearby hill. Excavation of the site uncovered finds dating to the early, middle and late Neolithic. Archeologists named the site “Dapenkeng5” and the early finds as belonging to the “Dapenkeng Culture,” estimating it to have been in use roughly between 6,500 and 5,000 years ago, which makes it Taiwan’s earliest known Neolithic site.

In light of Dapenkeng’s importance to research on prehistoric Taiwan, the Ministry of Culture, which is responsible for archeological sites, designated it a National Archeological Site. It is hoped that this will ensure the site is better preserved.

Image TM_02_01_0027 The Dapenkeng site

Image TM_02_01_0028 Hillside location of the Dapenkeng site

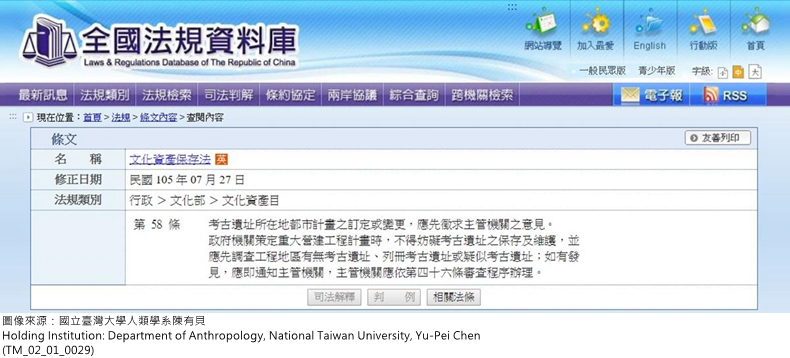

Image TM_02_01_0029 Laws relating to the preservation of archeological sites

3.3. The origins of the Dapenkeng Culture

Archeologists have found Dapenkeng sites to be common along Taiwan’s western coastal plains or hills near the sea. The sites situated along the west coast are older than those on the east coast. This phenomenon possibly indicates that more migrant groups landed on the west coast, and perhaps mainly originated from China’s southeastern coastal region. The finds that have been unearthed show that there were perhaps some similarities between prehistoric cultures on either side of the Taiwan Strait at that time. These similarities include the decorative cord markings on the surface, or parallel markings on necks of pottery vessels found on both sides of the strait, that would seem to indicate a cultural connection.

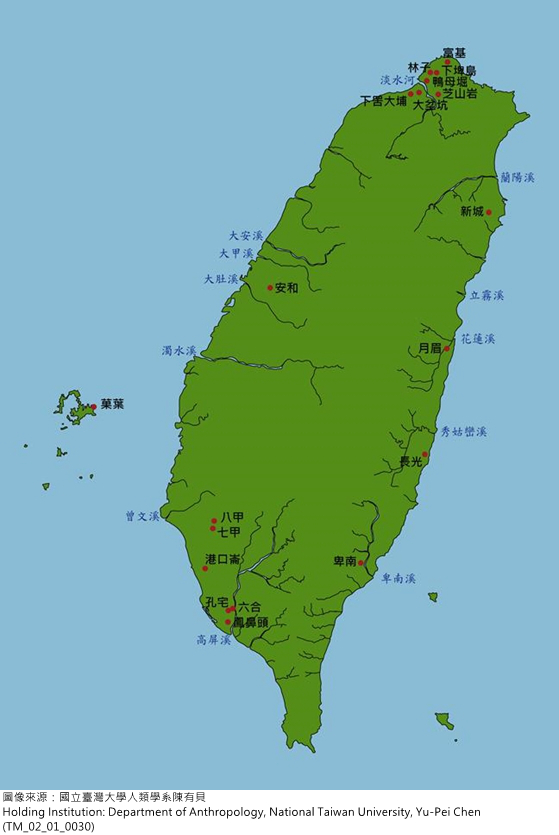

Image TM_02_01_0030 Distribution of Taiwan’s important Dapenkeng sites

Image TM_02_01_0031 Pottery fragments visible on the surface of a Dapenkeng site

Image TM_02_01_0032 Cord-marked pottery found at a Dapenkeng site

3.4. Early ways of life

If we wish to understand how Taiwan’s earliest Neolithic people lived, we must seek answers in the Dapenkeng Culture. Archeological surveys and research suggest that the people of the Dapenkeng Culture lived on elevated areas near river mouths or of the coastal plains, could make pottery or polished stoneware vessels, used tree bark to make cloth, or spun it into thread to make clothing. They relied not only on hunting and fishing for survival, but had also developed small-scale garden agriculture.

Agriculture was an important development in the evolution of humankind, and is regarded as a revolution in lifeways. The development of farming meant that people could more effectively control food resources. Improved farming techniques helped to increase yields, and allowed the labor of a small number of people to feed a larger population. The manpower released by such innovations could then be redirected into non-production activities, allowing different aspects of culture to develop. An increase in spiritual activities in particular increased the complexity of social trends. This clearly shows how important of the development of agriculture was.

Image TM_02_01_0033 Impression of what life was like at the river mouth for early peoples

3.5. Early farming methods in Taiwan

In the past, due to limited archeological data6, we could only make a common sense deduction that Taiwan’s earliest agriculture was probably the cultivation of rhizome crops—this is a farming method commonly seen in the warmer climates of South China and Southeast Asia, in which crops such as taro and tubers are mainly grown. This phase of farming is known as low-level agriculture, due to its convenience, simplicity, and the ease of harvesting.

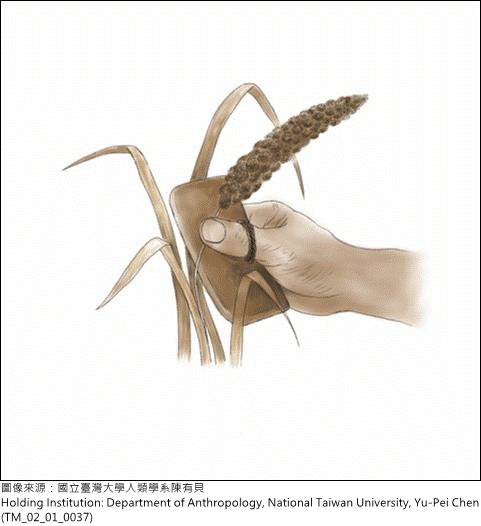

Later, at the Nanguanli and Nanguanli East sites in the Southern Taiwan Science Park in Tainan (roughly dating to the late Dapenkeng cultural phase), archeologists discovered traces of ancient rice and millet cultivation. This was direct proof that grain crops were already being cultivated at that time. This kind of farming activity is referred as “high-level agriculture.” Although it requires relatively complex production techniques and processes, the large and stable production yields and easily conserved foods leads to more stable and rapid social development.

Image TM_02_01_0034 A modern taro field

Image TM_02_01_0035 A modern millet field

Image TM_02_01_0036 Prehistoric agricultural tools: polished stone knives

Image TM_02_01_0037 Impression of picking an ear of millet with a stone knife

3.6. Prehistoric agriculture in Taiwan among the East Asian sea islands

To summarize agriculture on the Southeast Asian sea islands, farming began in Japan 3,000 years ago; on the Ryukyu islands, about 1,000 years ago; in the Philippines, about 4,000 years ago; and in Taiwan about 6,000 years ago. It therefore isn’t hard to imagine the uniqueness and importance of agriculture in Taiwan.

A special feature of ancient farming in Taiwan was the cultivation of both millet and rice.

Millet is a northern crop that is mainly cultivated in East Asia’s Yellow River basin at latitudes of around 35 degrees north. But since prehistoric times, millet has also been grown on the island of Taiwan, which lies at a latitude of 22 to 25 degrees. Taiwan’s millet cultivation has been practiced continuously down to present-day indigenous Taiwanese peoples, who regard a sacred crop. Rice cultivation, on the other hand, was more commonly practiced in the south. In recent times, researchers have used DNA analysis to distinguish a number of rice varieties7, hoping to understand their origins and dissemination routes.

Generally speaking, there is a close correspondence between patterns of agriculture and social development. We can therefore crudely infer that if agriculture was highly developed in prehistoric Taiwan, then there were possibly corresponding organizational structures and systems of work. For example, the existence of a central authority in the area or village, as well as a distribution mechanism, which allow effective production, while at the same time enabling the smooth operation of social structures.

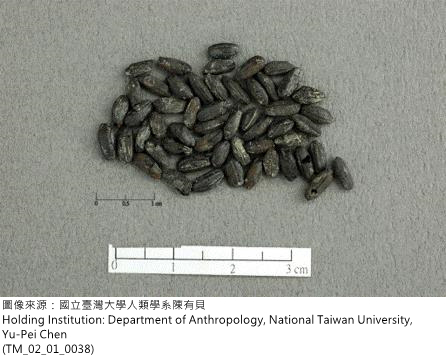

Image TM_02_01_0038 Prehistoric rice

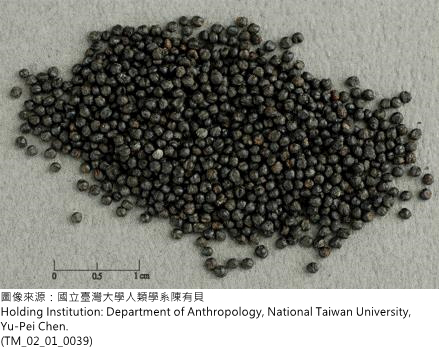

Image TM_02_01_0039 Prehistoric millet

3.7. After the early Neolithic

Following the Dapenkeng Cultural Phase, Taiwan entered the mid-Neolithic period of development, during which diversity was, unlike previously, an important indicator.

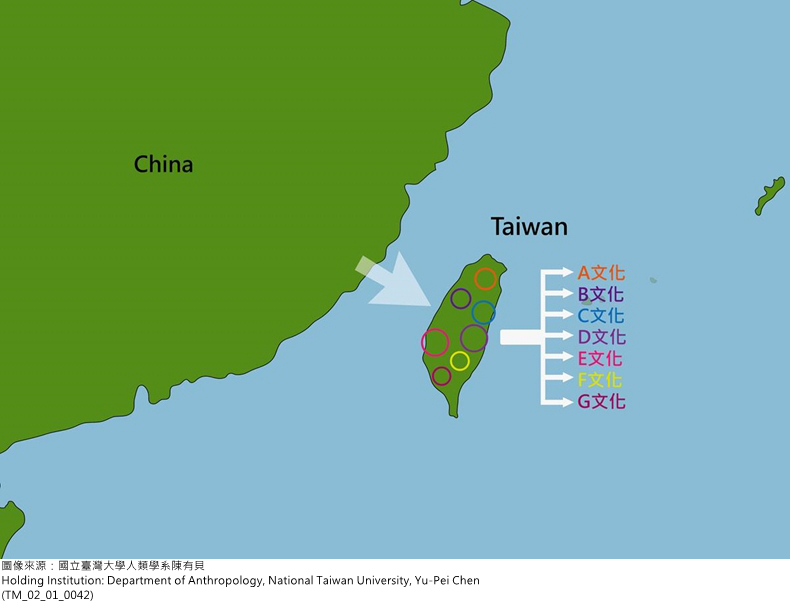

Despite not being a large island, Taiwan is still home to at least 20 culturally8, socially and linguistically distinct indigenous peoples. We can infer from archeological research that this level of complexity had already appeared as far back as the mid-Neolithic.

On the basis of archeological finds, researchers are roughly able to divide Taiwan into northern, central, southern, eastern, and mountain cultural geographies. Each area was sufficiently culturally distinct to support the existence of different lifeways at the time.

Image TM_02_01_0040 Illustration of the distribution of indigenous Taiwanese

3.8. Multiple migrations or divergent adaptation?

Scholars presently offer two explanations for the existence of the many different ethnic groups on the island of Taiwan: The multiple migrations hypothesis, and divergent adaptation hypothesis. The multiple migrations hypothesis posits that since the Neolithic times there have been many migrations to Taiwan. These occurred at different times, originated from different locations, and settled in different regions of Taiwan, and so naturally resulted in the existence of different ethnic groups on the island. The divergent adaptation hypothesis argues that after the arrival of the earliest group (the Dapenkeng Culture), people moved into the varied regional geographies: high mountains, low hills, basins, and plains. Communities living in these different environments became isolated from each other, and over a very long period deeply adapted to their local ecologies. Eventually they became Taiwan’s different ethnic groups.

But in reality, perhaps this question cannot be resolved with a single model of migration. Each ethnic group developed in its own way, and was impacted differently by the natural environment, time, and historical events.

Image TM_02_01_0041 Reason for Taiwan’s many ethnic groups: multiple migrations theory

Image TM_02_01_0042 Reason for Taiwan’s many ethnic groups: divergent adaptation theory

3.9. Historical factors or ecological adaptation?

Taiwan’s prehistoric sites are scattered across different geographies, and have also been found at high elevations in the mountains (e.g. Qubing). We are reminded of the fact that many indigenous people also live in Taiwan’s high mountains. There are also different explanations for this phenomenon. One theory suggests that when early humans first arrived in Taiwan, they originally chose to live on the coastal plain, but the arrival of a succession of later migrations drove these original plains dwellers up into the mountains. The main evidence for this hypothesis is the discovery of many early prehistoric sites along the coastal plains, proving that groups of ancient people did once live on there. But there is a lack of clear evidence to explain why they moved into the mountains; there is only the fact that from time to time skeletal remains of battle victims are found at sites, which to some degree reveals incidents of armed conflict between groups.

Another theory is that before migrating to Taiwan, they lived in the mountains, and having lived there for a long period, after arriving in Taiwan they naturally sought out similar places suited to their traditional way of life. Until modern times there were still many indigenous people who preferred to live in the mountain forests, only later relocating to the plains in more recent times due to outside pressures and influences.

Image TM_02_01_0043 Skeletal remains of a battle victim

Image TM_02_01_0044 The Qubing site

Image TM_02_01_0045 The Qubing site

Image TM_02_01_0046 The Qubing site

3.10. Birthplace of the Austronesian languages?

The so-called Austronesian languages are the main group of languages now spoken on the islands of the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Linguists have classified them in the same language group because of their grammatical, lexical, and phonological similarities.

But why do these linguistic similarities exist? The most direct answer is that their speakers originated from the same region, and so continue to follow the same linguistic tendencies and display the same ways of expression, despite having left their homeland. As for the the homeland of the Austronesian languages, some linguists have hypothesized that Taiwan was very possibly their earliest origin9, which aroused considerable interest in this question among Taiwan’s scholarly community.

There is key archeological and anatomical evidence for and against this linguistic theory, but at present scholars do not agree on any conclusion.

Image TM_02_01_0047 The spread of the Austronesian languages

Matisoo-Smith 2015 “Tracking Austronesian expansion into the Pacific via the paper mulberry plant”)

3.11. Evidence to support Taiwan as the origin of the Austronesian languages

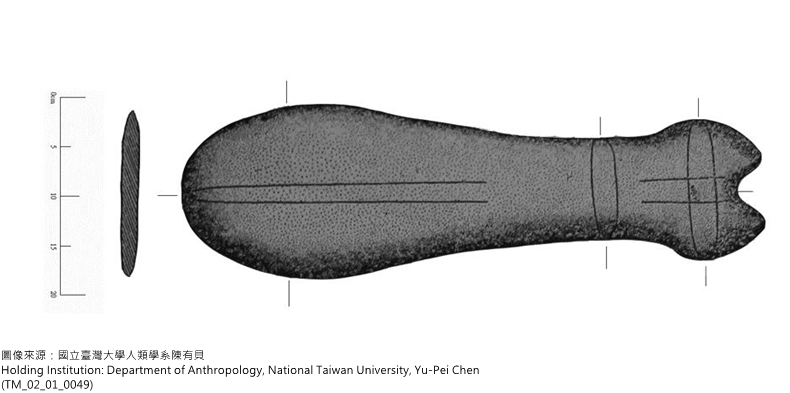

One piece of evidence commonly mentioned when it comes to proving the affinity between Taiwan and the other Pacific islands is the patu. The patu is a symbolic club held by Austronesian peoples (particularly the Maori) during ceremonies. In the 1930s, research suggested a possible affinity between patu and “polished stone axes” unearthed at archeological sites in Taiwan. For this reason the latter are often called patu or patu-shaped stone implements. Judging by the fine quality of their external finish, they probably had no everyday practical use, but carried symbolic meaning like the Pacific patu. However, further research is needed to clarify whether these unearthed implements are in fact the original form or forerunner of the Pacific patu.

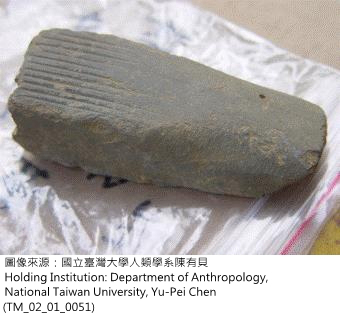

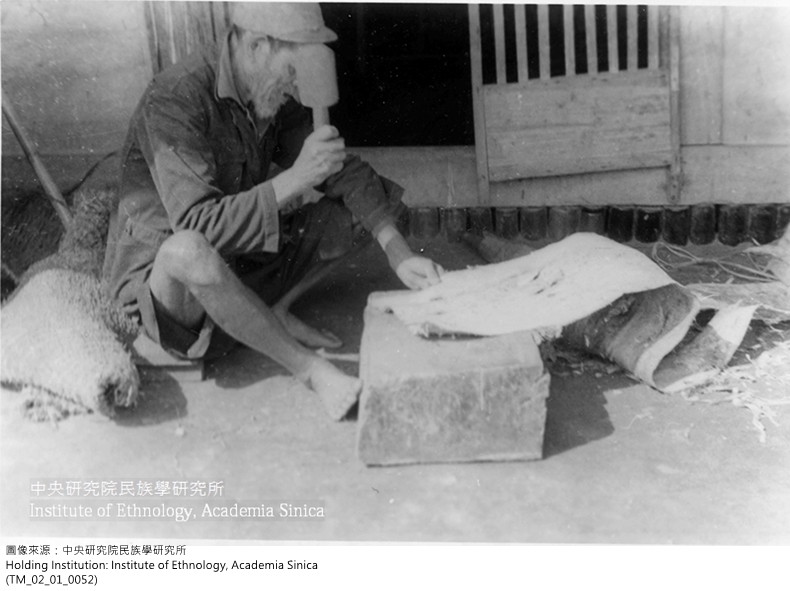

The tapa beater is another piece of evidence that can link prehistoric Taiwan and the Pacific islands. These implements are often seen at Neolithic sites in Taiwan, and because they are similar in shape to tools now used by Pacific peoples for making tapa cloth, archeologists speculate that they served the same function. However, these prehistoric tapa beaters found by archeologists are made of stone, whereas those used by modern peoples are made of wood. Further experimental analysis is needed to more fully verify whether the two implements were used for the same purpose. Prehistoric tapa beaters have been found not only in Taiwan, but also in surrounding regions, such as South China and Southeast Asia, which demonstrates that it was a widely used tool.

Image TM_02_01_0048 Prehistoric tapa-shaped stone tools

Image TM_02_01_0049 Fine quality tapa-shaped object

Image TM_02_01_0049 Impression of ceremonial tapa use by Pacific peoples

Image TM_02_01_0051 Tapa beater

Image TM_02_01_0052 Man beating tapa bark

3.12. Evidence against Taiwan as the origin of the Austronesian languages

On the other hand, there is also evidence to show that there is in fact no direct link between Taiwan and the Pacific Austronesian languages10. A case in point are the double-grooved stone sinkers commonly used in Neolithic Taiwan. These net sinkers were widely distributed across prehistoric Taiwan. They were elongated pebbles with a groove carved around their circumference at each end, which were tied to the edge of a fishing net called a cast net. Their shape and weight allowed the net to be effectively cast out into the water to catch fish. The cast net was a highly efficient invention. The archeological record shows that they were widely used over a long period in prehistoric Taiwan. Supposing groups of people did indeed migrate from Taiwan to other islands, then we would expect those people to have taken their most efficient piece of fishing equipment with them, and consequently we would certainly be able to find them at archeological sites on other islands. However, these sinkers have never been found at any such site outside of Taiwan.

To the contrary, an abundance of ancient fishing hooks have been found on many Pacific islands, which illustrates the fact that pacific Austronesians have long been extremely fond of line fishing; it is only in Taiwan that very few fishing hooks have been found from prehistoric times. This evidence would seem to suggest that there was no active migration from Taiwan to other islands in prehistoric times.

Image TM_02_01_0053 Deploying a cast net

Image TM_02_01_0054 Deploying a cast net

Image TM_02_01_0055 Modern net sinkers

Image TM_02_01_0056 Prehistoric double-grooved sinkers

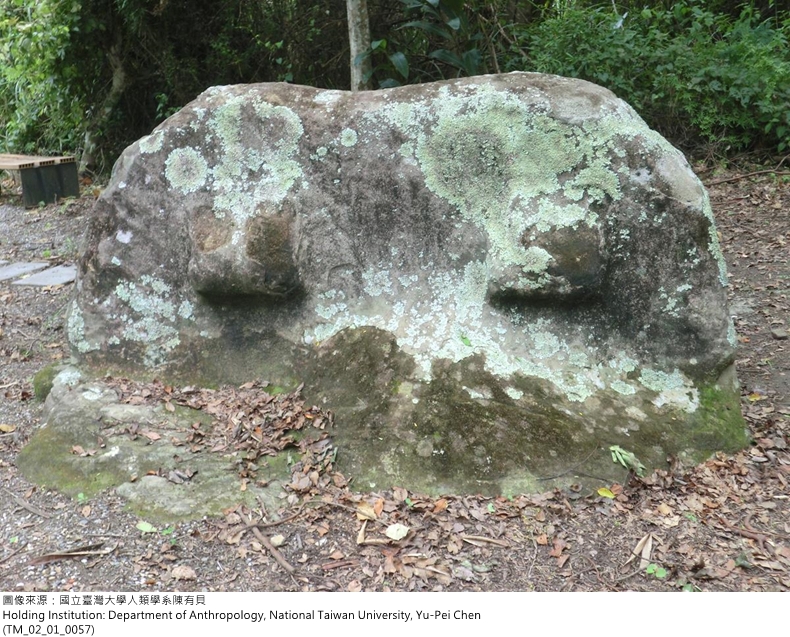

3.13. Taiwan’s prehistoric megalithic culture

Megalithic culture is an example of the many cultures of Neolithic Taiwan

The term “megalith” usually refers to a structure made from large worked stones. It is a phenomenon shared by human societies in many parts of the world.

There are also megaliths in Taiwan, mainly distributed in the east. Types include stone pillars, walls, coffins, wheels, as well as standing stones. The majority of research concludes that they were probably created by prehistoric Taiwanese peoples themselves.

But creating these monoliths would have been strenuous and time-consuming work, and as far as we can see they serve no practical function. So why painstakingly work these large stones or boulders? The answer is that monoliths have a spiritual significance connected with cults or religions, and therefore of course can’t be evaluated by their economic benefit alone. The appearance of this kind of stonework is frequently related to agricultural development of the time—in other words, a high level of agricultural development freed up manpower that enabled people to create more objects connected with their spiritual culture.

Image TM_02_01_0057 Stone wall

Image TM_02_01_0058 Stone pillar

Image TM_02_01_0059 Stone coffin

Image TM_02_01_0059 Stone coffin

Image TM_02_01_0061 Modern megalith worship

4. The Iron Age

4.1. The third major migration?

Taiwan’s Iron Age began around 2,000 years ago and ended around 300 years ago. It was followed by the transition from the prehistoric to historical age, when written records begin.

The content of many Iron Age sites markedly differs from earlier sites. There is research that argues that at this time another group of new migrants arrived in Taiwan after crossing the sea from Southeast China. They brought with them their ironwork and a new way of life, and were culturally distinct from the existing Neolithic peoples. If true, it was the third major prehistoric migration to Taiwan. Looked at from a mainland East Asian perspective, several theories can be found in support of this migration hypothesis. The main grounds for this support is social unrest on the mainland 2,000 years ago, from which a number of peoples fled. As people in northern mainland East Asia are known to have migrated to the Korean peninsula and the Japanese archipelago11, it seems quite reasonable to suggest that people living in the south could have crossed the sea to Taiwan.

There are also scholars who argue that Taiwan’s Iron Age culture began when people in Taiwan took up the use of iron tools, which led to a great transformation in lifestyle, and produced a culture that differed in substance from the Neolithic period. One piece of evidence in support of this hypothesis is that there are several different kinds of Neolithic find that continue to turn up at Iron Age sites. In other words, these later people were a continuation of the original Neolithic peoples, it was only their way of life that had changed.

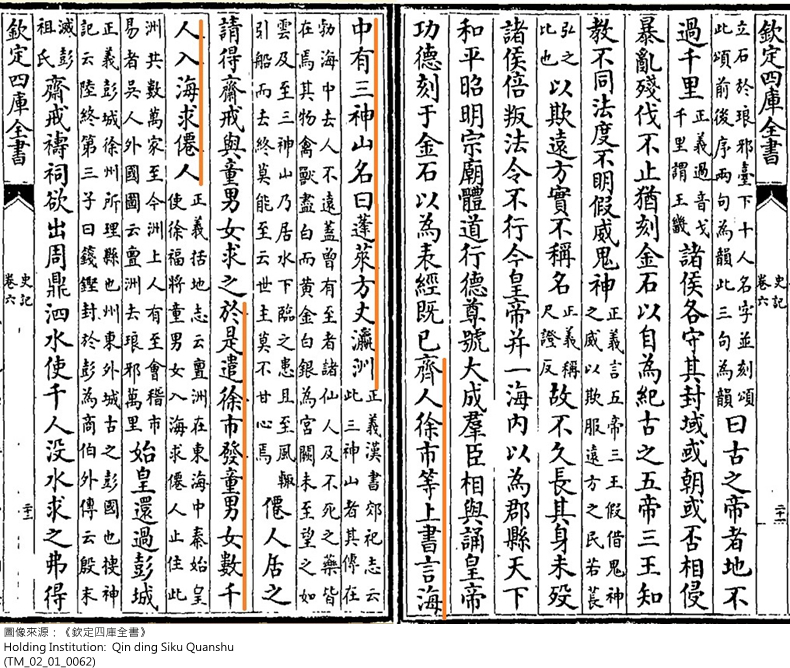

Image TM_02_01_0062 Ancient materials relating to the legend of Xu fu.

4.2. Where did this ironware come from?

Where did Taiwan’s prehistoric ironware originate? Early on it was mainly argued that it was imported from elsewhere, whether through trade or brought in directly by migrant peoples. This view was formulated based on the observation that modern indigenous Taiwanese had no iron forging technology. Since this was the case, then of course their Iron Age ancestors would not have known how to forge iron either, so all ironware was probably imported. However, this purely theoretical idea was overturned by real archeological finds.

Since the 1990s, suspect materials such as pieces of iron from the ironmaking process gradually began to turn up at archeological sites. Among these, the remains of structures used for smelting iron excavated at the Shisanhang site12 were direct proof that iron was smelted in Taiwan during ancient times. Researchers then began to examine the complete picture of prehistoric iron forging in Taiwan. Recently even more direct evidence has been unearthed in the form of metal molds used for casting iron at archeological sites such as Jiuxianglan. This has overturned the traditional theory that prehistoric Taiwanese peoples were completely unable to forge iron.

Image TM_02_01_0063_01 Castings found at the Jiuxianglan site

Image TM_02_01_0063_02 Castings found at the Jiuxianglan site

However, there are few sites where evidence has been found proving iron forging. Even if the people of prehistoric Taiwan did have iron forging technology, that does not mean that all ironware was made on the island at that time; surveying the ironware finds made at Taiwan’s archeological sites, most are clearly quite close in form to similar objects unearthed along the southeastern coast of China, which strongly suggests that a portion of the ironware originated there.

4.3. The changes brought by ironware

Seen from the point of view of technological history, from the use of wood, bone, and stone tools during the earliest times, to pottery, metal, and glass, each innovation in materials brought with it social and cultural changes. Ironware was no exception, as reading the historical records of any culture in the world will confirm.

Iron appeared in Taiwan around 2,000 years ago. At that time there were no written historical records, and so we can only examine the cultural and social impact iron had through changes in the archeological record. At first glance, besides a small number special sites that show iron and stone used side by side, at the majority of sites where iron tools have been found there were only a very limited quantity and variety of stone tools present, indicating that iron tools had essentially already supplanted stone tools. This is not at all hard to understand: although stone is a solid material, it is not easy to reshape, whereas tools made of iron are not only solid, but can also be freely molded to the maker’s design. In particular it allows the manufacture of sharp-edged blades. These advantages drove the widespread use of iron tools13.

History records only one sentence describing indigenous ironwork: “Everything is made with the knife at the waist.” It is a description that vividly captures the functional convenience of iron tools, and their importance in the lives of indigenous people.

Image TM_02_01_0064 Iron knife unearthed by archeologists

Image TM_02_01_0065 Iron knife unearthed by archeologists

Image TM_02_01_0066 Iron knife unearthed by archeologists

Image TM_02_01_0067 Indigenous person wearing an iron knife at the waist

4.4. The rise of maritime trade

The early part of the Iron Age brought with it social change mainly due to the innovation of iron forging technology. By the late Iron Age, maritime trade brought another wave of transformations in lifeways.

Taiwan is an island open to approach from every direction. From about the fifteenth century, a number of countries began to actively conduct trade in Maritime Southeast Asia, a trading area into which Taiwan also became incorporated.

There is no lack of imported objects in the archeological sites of this period. In particular, sites closer to the sea, such as Shisanhang, Hanben, and Jiuxianglan, tend to have more of an abundance of imported objects than inland sites. The majority of the more commonly seen imported objects made from ceramics, metal, and glass, generally came from China. It is also not uncommon to find products from regions such as Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, and even the mainland West.14 What kinds of things were used to trade with these outsiders? There is still a lack of archeological evidence, but if more modern documents are any clue, things like deer skins, deer meat, rice, or salt are all possibilities.

Image TM_02_01_0068 Imports unearthed by archeologists: glass

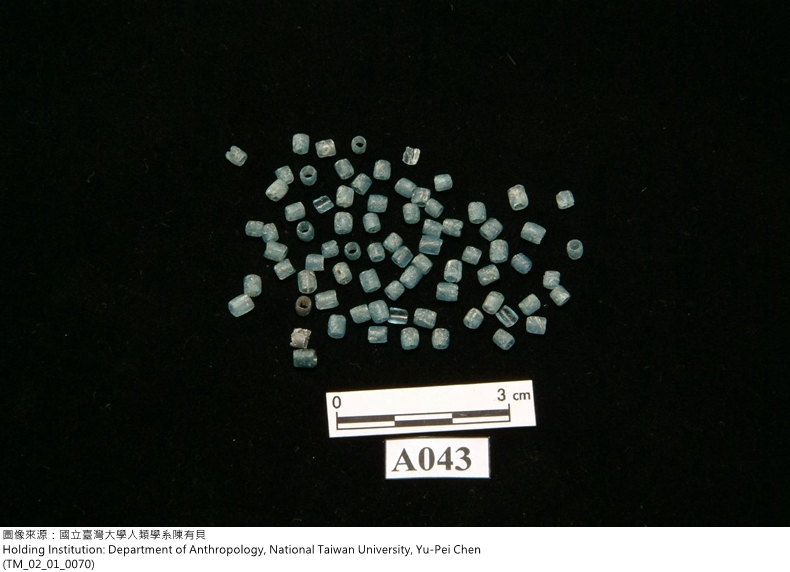

Image TM_02_01_0069 Imports unearthed by archeologists: decorative beads

Image TM_02_01_0070 Imports unearthed by archeologists: decorative beads

Image TM_02_01_0071 Imports unearthed by archeologists: decorative beads

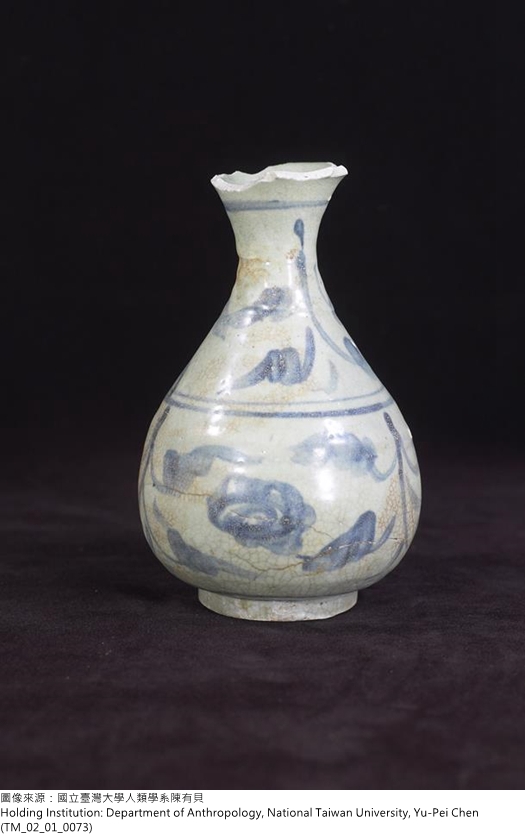

Image TM_02_01_0072 Chinese ceramics unearthed by archeologists

Image TM_02_01_0073 Chinese ceramics unearthed by archeologists

Image TM_02_01_0074 Chinese ceramics unearthed by archeologists

Image TM_02_01_0075 Southeast Asian ceramics unearthed by archeologists

Image TM_02_01_0076 Southeast Asian ceramics unearthed by archeologists

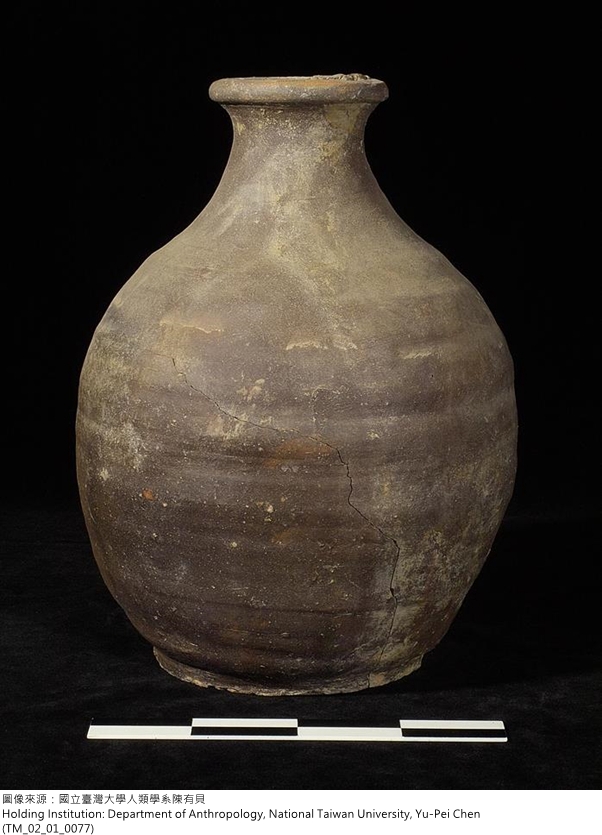

Image TM_02_01_0077 Imported ceramics

4.5. The influence of trade

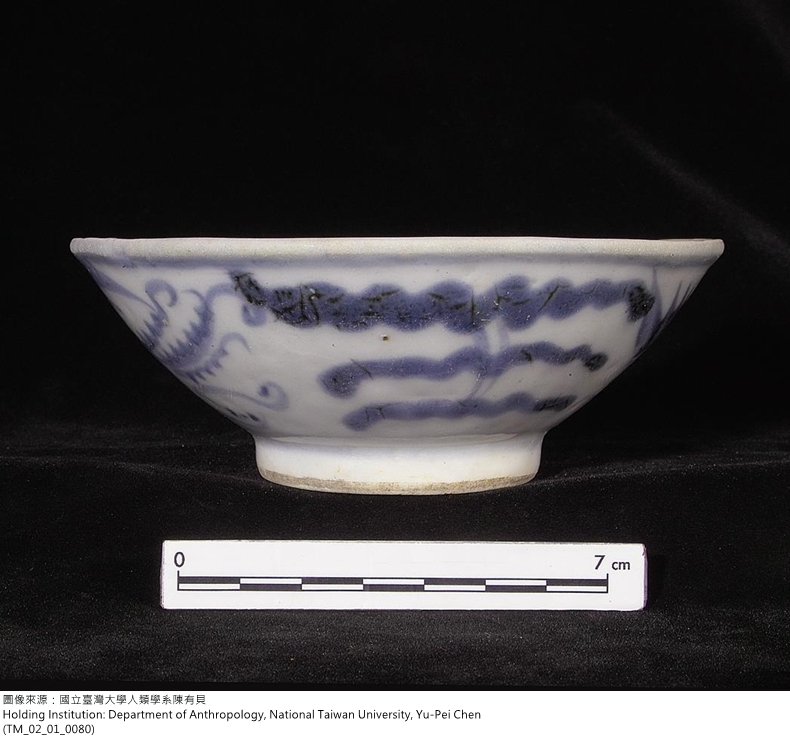

Superficially, the new things of every description brought by trade made living conditions more materially plentiful and varied; however in essence trade also brought in outside culture, and brought about a change in values, having an even greater impact on traditional culture than material culture. Archeological research has uncovered no lack of examples. For example, the archeological finds from the Qiwulan site situated on the Yilan plain show changes in eating and drinking behaviors. Many early eating and drinking utensils were made of traditional pottery, but later on Chinese bowls, plates, and spoons were often used instead15.

More significantly, these changes can be seen in the grave goods accompanying burials. At the Qiwulan site traditional earthenware jars are used as grave offerings in earlier burials, while imported ceramics are more often used as offerings in burials of a later period. This kind of change reflects changes in the value system.

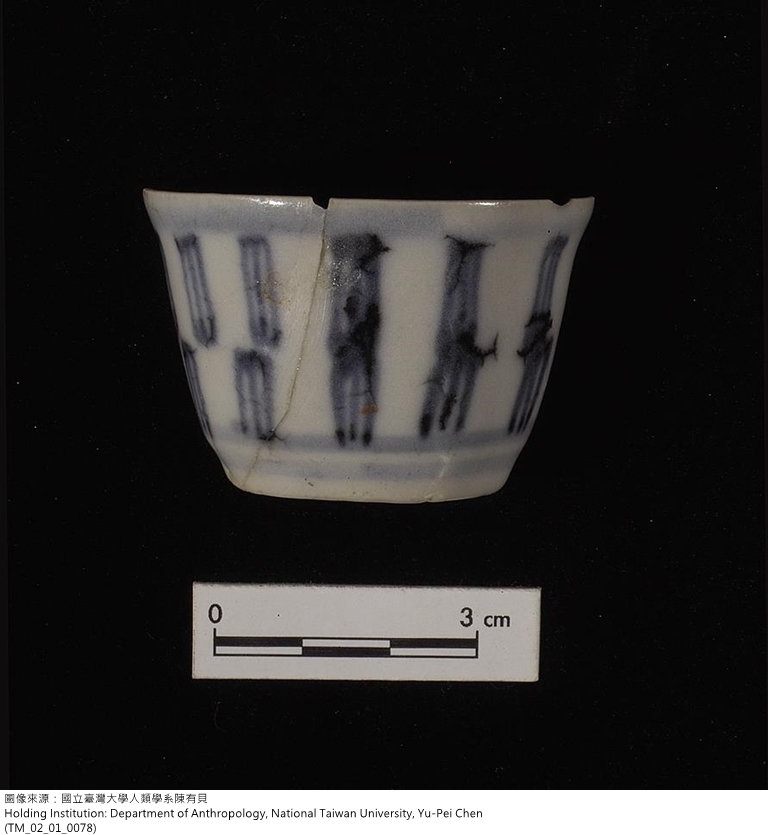

Image TM_02_01_0078 Chinese cup

Image TM_02_01_0079 Chinese spoon

Image TM_02_01_0080 Chinese bowl

Image TM_02_01_0081 Chinese dish

Image TM_02_01_0082 Chinese plate

Image TM_02_01_0083 Chinese goods used in a burial

4.6. Taiwan’s prehistoric inhabitants: ancestors of today’s indigenous peoples?

Generally speaking, Taiwan’s prehistoric sites were left behind by the ancestors of today’s indigenous peoples. In other words, Taiwan’s prehistoric inhabitants are none other than the ancestors of modern indigenous Taiwanese. However there are many ethnic groups on the island of Taiwan with complex interrelationships, and so it is difficult to clarify the specific origin of any one of them. Moreover, so-called ethnic groups are a cultural construct, upon which time and situation produce changes. The longer time passes, the harder it gets to delve into the question of ethnic origins.

This being so, if we want to investigate the ancestors of indigenous Taiwanese, it is difficult to make connections to Neolithic culture because of the distance in time. Comparatively speaking, being closer to the historical period, Iron Age culture is much more likely to provide answers.

In recent years, archeological research has begun to make a number of breakthroughs with regard to this question16. For example we can now say with some certainty that the Shisanhang site in northern Taiwan was left behind by the ancestors of the Ketagalan people, the Qiwulan site on the Lanyang plain belonged to the Kavalan, and the Jiuxianglan site on the Taitung coast was created by the ancestors of the Paiwan. The main archeological proof, besides these sites being located in the right place and being of the right age, is that sometimes the finds unearthed there are objects or designs that are symbols still used by the modern tribe. Ethnological records show that the figure wearing a tall headdress motif that has been unearthed at the Qiwulan site was the main symbol used by the Kavalan to represent their ancestors. Another example is the hundred-pace viper motif unearthed at the Jiuxianglan site, which is similar to a symbol used by modern Paiwan people.

Image TM_02_01_0084 Pottery decorated with a primitive 100-pace viper design unearthed at the Jiuxianglan site

Image TM_02_01_0085 Stone object decorated with a primitive 100-pace viper design unearthed at the Jiuxianglan site

Image TM_02_01_0086 Paiwan pottery jar decorated with a 100-pace viper design

4.7. Jiushe—representative examples of a protohistoric period site

Before the prehistoric-historic transition, there was a short period for which there are no historical records, but the history of which can be retraced through the memories of the tribe. Archeologists refer to this as the protohistoric period.

The best example of protohistoric archeological sites in Taiwan is the jiushe. The name ‘jiushe’ means ‘the old village’, referring to the site of an old village where the local indigenous people no longer live. These sites are usually several hundred years old, and no one knows who created some of them, but others can be roughly traced through tribal legends or memories. Jiushe archeology is the key to connecting modern indigenous Taiwanese to prehistoric sites, and is a characteristic feature of Taiwanese archeology.

Due to the impact of large-scale modern and contemporary development, most jiushe on the plains are lost forever. But a number still remain among the mountain peaks, in particular in the southern mountains there is no lack of houses built out of large, heavy pieces of slate. The majority of jiushe have been generally abandoned and left to ruin, but the still allow us to glimpse how early indigenous settlements looked.

Image TM_02_01_0087 Ruins of a jiushe in the mountains of southern Taiwan

Image TM_02_01_0088 Ruins of a jiushe in the mountains of southern Taiwan

Image TM_02_01_0089 Ruins of a jiushe in the mountains of southern Taiwan

4.8. Historical period archeology

The main task of traditional archeology was to research societies with no writing system. Societies that have writing systems fell into the realm of historical research. Later, however, scholars discovered that historical documents are not without their problems. Most of Taiwan’s early historical documents, for example, were written by other peoples (not indigenous Taiwanese), whose records are sometimes biased, and sometimes overly subjective. As a consequence, there is also a need for archeologists to research the historical period.

In light of this understanding, Taiwanese archeologists no longer focus only on prehistoric period finds and research, but have also begun to show interest in sites and relics that extend into the historical period.

Taking the Qiwulan site on the Lanyang plain as an example, the burials of its late phase date to the historical period. Comparative studies using Japanese language materials, such as the Kavalan Gazetteer, allow us to fully understand how indigenous society really was at that time.

Image TM_02_01_0087 The Kavalan Gazetteer

4.9. Taiwan’s neighbors: the importance of regional archeology

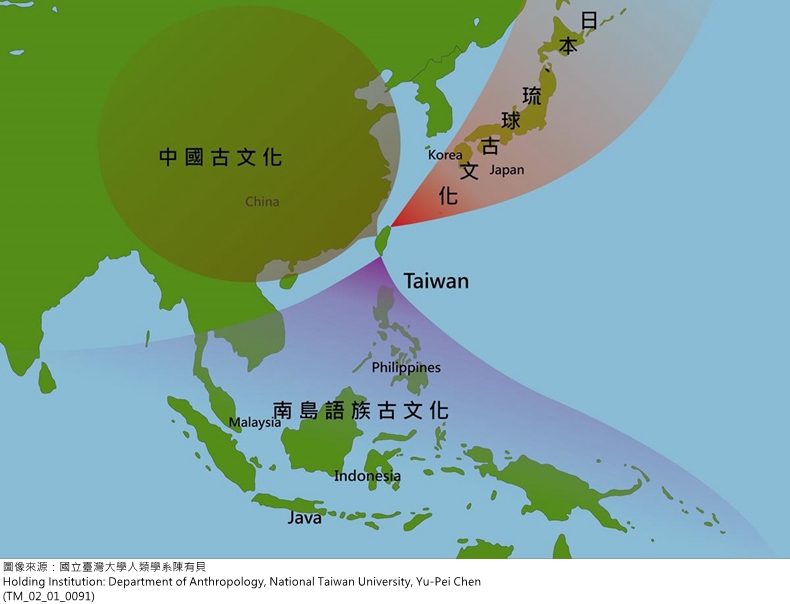

The East Asian mainland lies to Taiwan’s west, the islands of the wide Pacific to the east. To the north are the Ryukyu Islands, to the south the islands of Maritime Southeast Asia. The island of Taiwan is therefore a gateway between the mainland and the ocean. It is also a place where East Asian peoples and cultures have intersected.17 This was true particularly in the prehistoric period when there were no national borders, and so inevitably fewer borders and barriers to the distribution and expansion of culture than today.

Some relics (e.g. stone knives, and pennanular jade rings) made in prehistoric Taiwan have also been unearthed at archeological excavations in East Asia and other regions, which is a sign that there were migrations of people and culture, contact with other regions, or trade between them. Thus if we want to understand the essence and roots of our own culture, we must never neglect to research Taiwan’s neighboring regions.

Image TM_02_01_0091 Taiwan lies at the intersection of ancient cultures

Image TM_02_01_0092 distribution of pennanular jade rings