1. The History of Medicine and Sanitation in Taiwan

Fan Yan-qiu 1

1.1. Taiwan’s Tropical Climate and the Land of Disease

Taiwan is located in the subtropical region. From ancient times it has been known as “the land of miasmal diseases.” During the Qing dynasty, local gazetteers and the writings of the literati often mention that there is a miasma in the land and water here. Those who traveled about in Taiwan seemed to easily contract a disease. During the Ming and Qing dynasties, troops stationed here also recorded that Taiwan is a place where “disease is rampant.” In 1874, the Mudan Incident forced Qing China to send Shen Baozhen and troops to Taiwan to defend it. While these troops never engaged in combat with the Japanese, “many of the troops, who came from all over China, contracted diseases and several thousands died.” Actually, the Japanese aggressors were also subject to the onslaught of tropical diseases during their occupation of southern Taiwan. When the entire incident was over, the Japanese had 11 soldiers die due to fighting and 547 die due to disease 2. Thus was the serious toll of disease. At the time, the Japanese did not understand this type of sickness. They simply called it the “Taiwan fever,” which was sufficient to portray the danger of the more tropical climate in Taiwan.

Shen Baozhen

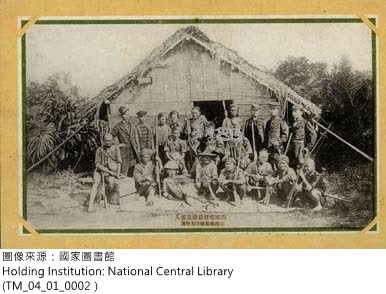

A picture of the Japanese troops led by Lieutenant-general Saigō Jūdō that seized southern Taiwan

What the Chinese literati called “miasmal diseases” and the Japanese army called the “Taiwan fever” are actually contagious diseases due to the natural environment in Taiwan. In 1895 after Japan took control of Taiwan, the veil of mystery shrouding these diseases was gradually taken off as the Japanese brought with them modern medical practices from the West. Doing so also provided a way to enact effective prevention measures and propel Taiwan’s society into the modern age of public health.

1.2. The Japanese Invasion of Taiwan and the Outbreak of Communicable Diseases among the Japanese Troops

During the mid-19th century, the Japanese underwent the Meiji Restoration. After they had modernized, they began to mimic the West in expanding and invading other countries. From 1874 when Japan first invaded Taiwan to the First Sino-Japanese War in 1894, Japan became the newest imperialistic country in Asia. In May 1895, the China and Japan signed the Treaty of Shimonoseki, which ceded Taiwan. The Taiwanese people then founded the Republic of Formosa and fought against Japanese occupation. This battle is known as the Japanese invasion of Taiwan (or the Yiwei Battle) in modern Taiwan history.

The flag of the Republic of Formosa

In March 1895, Japanese troops invaded Penghu and in a short time had taken control of the islands. Casualties were minimal with only three dead and twenty-seven injured. However, troops stationed in Penghu were soon overtaken with an outbreak of disease, with cholera being the most severe. At the time there were a total of 6,194 troops; of these, 1,945 contracted cholera and 1,247 died. These soldiers were buried in a mass grave known as the Thousand Soldier Mound. This memorial stands as a witness to the devastating effects of disease on the Japanese army stationed in Penghu.

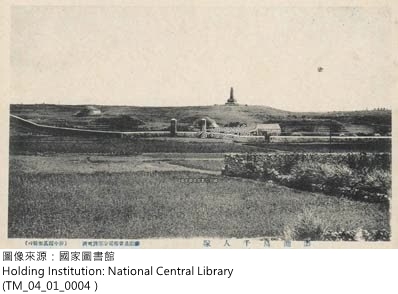

A mass cemetery at Penghu

The Taiwan Grand Shrine (Taipei)

Prince

Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa

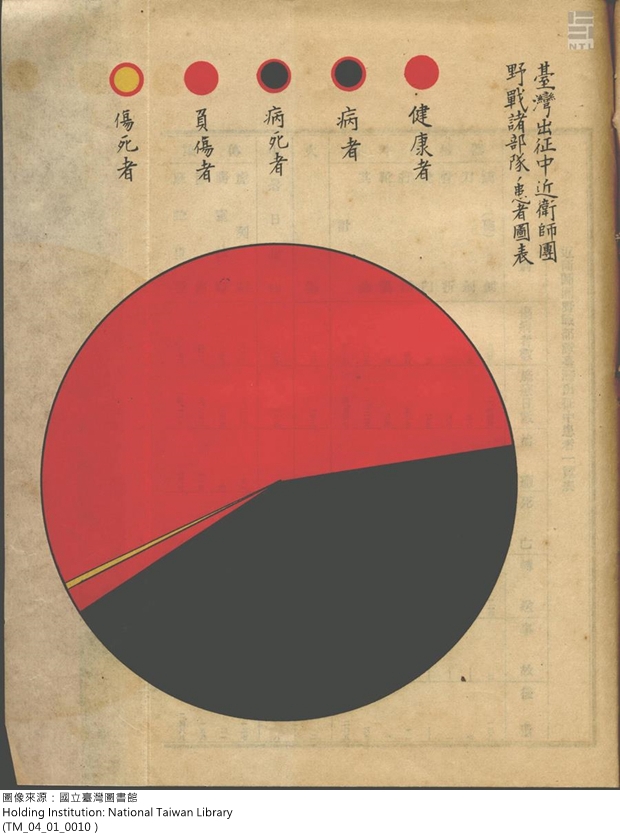

In May of the same year, Japan sent the imperial guard of Prince Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa to Taiwan to take over the assault. This led to the Battle of Taiwan. The greatest resistance that the Japanese encountered in this battle was not in Taiwan’s weaponry but in death from communicable diseases. As of November 1895, the battle had resulted in 164 dead in battle, 515 wounded, 4,624 dead from disease, and 26,094 sick with disease. The latter two numbers represent more than half of the troops mobilized for this battle. Furthermore, the number that died from disease is more than 28 times the number that died in battle. In looking at the statistics regarding the diseases contracted, the vast majority were communicable diseases, with cholera causing the most deaths and malaria infecting the most soldiers. In fact, Prince Kitashirakawa even died in Tainan 3. He was the first person from the Japanese royal family to die in Taiwan. His death led to the construction of the Taiwan Grand Shrine, with Prince Kitashirakawa as the main deity.

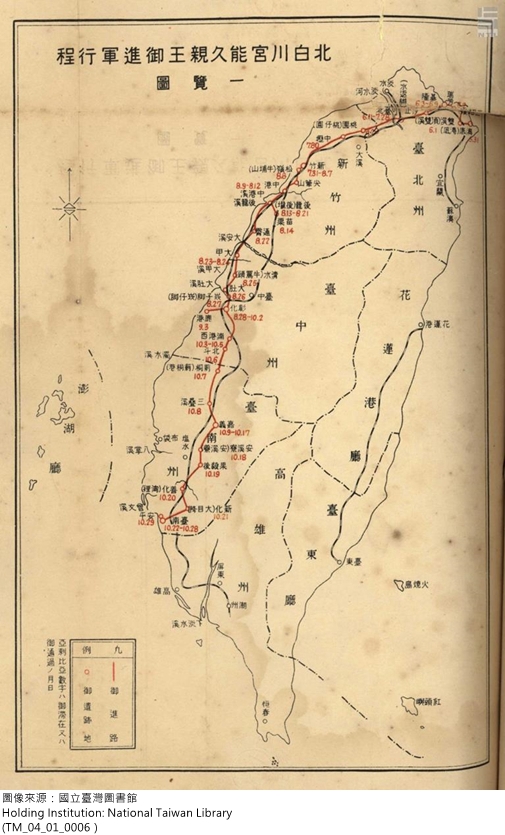

A Japanese drawn map of Prince

Kitashirakawa Yoshihisa’s route in attacking Taiwan

1.3. The Japanese Army’s Difficulties in Stopping an Epidemic and Its Repercussions

Why was the Japanese army subject to such devastating infectious diseases during the Japanese invasion of Taiwan in 1895? According to the analysis of army medic Horiuchi Tsugio, there were three primary reasons. First, the Japanese had only a limited knowledge of common diseases in Taiwan; since no investigation had been conducted into common illnesses and communicable diseases in Taiwan, they were unable to put effective prevention measures in place. Second, Taiwan lacked sanitary health facilities; a cholera outbreak was difficult to control due to a lack of drinking water system and no port and harbor quarantine system. Third, there was insufficient research into preventative medicine; at the time, bacteriology was still in its infancy and prevention and curative procedures were imperfect.

Army doctor

Horiuchi Tsugio

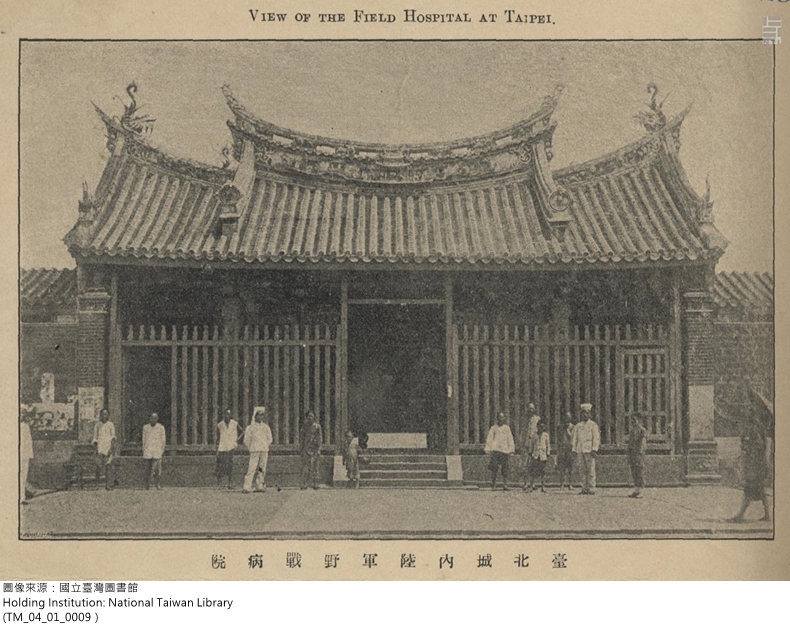

The army field operations hospital in Taipei

After the Meiji Restoration in the mid-19th century, the Japanese replaced traditional Chinese medicine with modern Western medicine. Horiuchi Tsugio approached the problem from a Western medical perspective, pointing out that research that had been done in the West on communicable diseases. Despite the revolutionary nature of bacteriology, it was still in its beginning stages. In addition, he also outlined the basic steps to prevent the spread of disease, including conducting scientific surveys of diseases, understanding how communicable diseases spread, and implementing critical sanitary facilities. Due to his experience in Taiwan, he also highlighted the fact that because the invasion of Taiwan was hindered by communicable disease, the most urgent yet difficult issue in ruling Taiwan was sanitation. As a result, the Governor-General of Taiwan placed high emphasis on improving sanitation during the beginning years of ruling Taiwan.

A health report of the Japanese imperial guard during the invasion of Taiwan

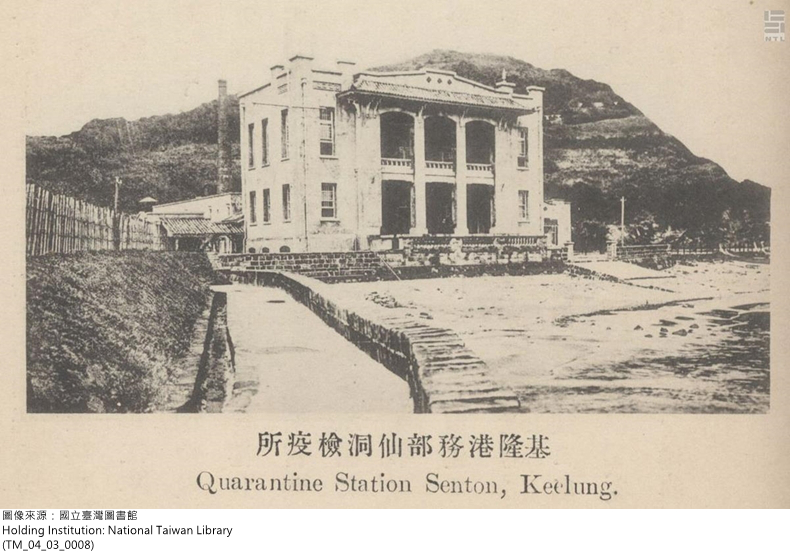

1.4. Sanitation Facilities to Prevent Communicable Disease from Entering Taiwan: Seaport Quarantine Stations

Cholera was the greatest cause of mortality in the Japanese invasion of Taiwan. This was in part because during the 19th century there were five worldwide outbreaks of cholera, which created a system in the Asia area. Therefore, the cholera outbreak among the Japanese army during the invasion was brought to Penghu and Taiwan by the army from elsewhere, most likely from Japan or the battlefields of the Sino-Japanese war. However, the spread of cholera in the 19th century has also been viewed as the “birth of sanitation.” It gave rise to the prevention and treatment of the disease, including carrying out quarantine to prevent it from entering from elsewhere and projects to improve public health (such as providing clean drinking water and disposing of sewage). In 1895, after Taiwan became Japan’s first overseas colony, it focused on establishing seaport quarantine measures to prevent the introduction of infectious diseases from elsewhere. In April 1896, the Office of the Governor-General drafted temporary measures for the quarantine of oceanic vessels at five ports. This marked the beginning of seaport quarantine in Taiwan. In August 1899, the Office of the Governor-General issued regulations regarding quarantine in Taiwan ports which were based off of quarantine laws in Japan. Thus, after Japan obtained national quarantine rights it replicated its quarantine system in Taiwan.

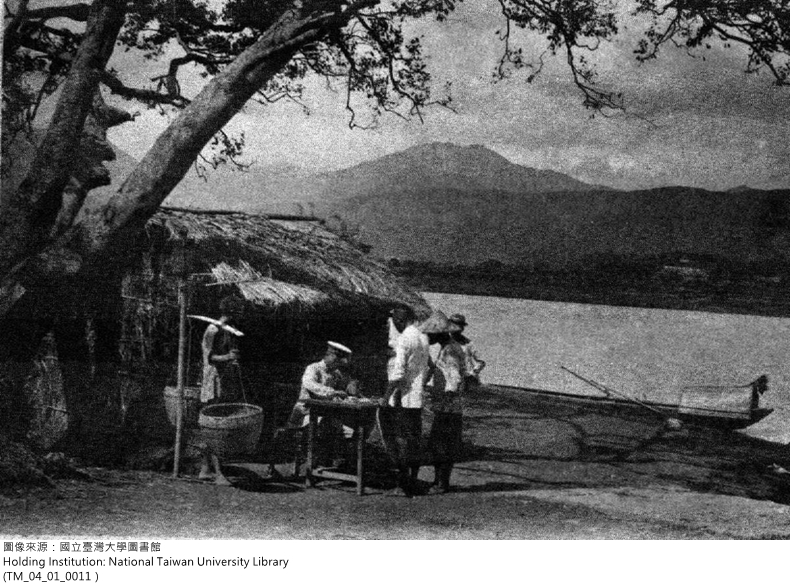

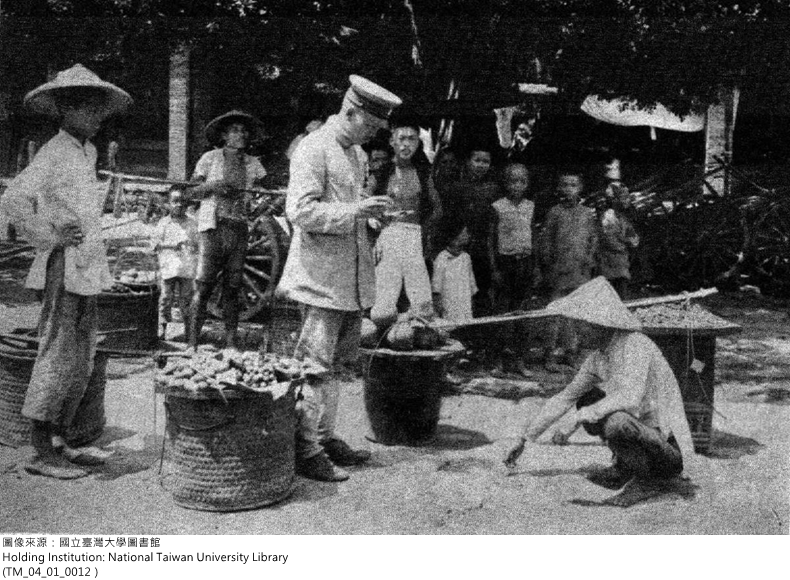

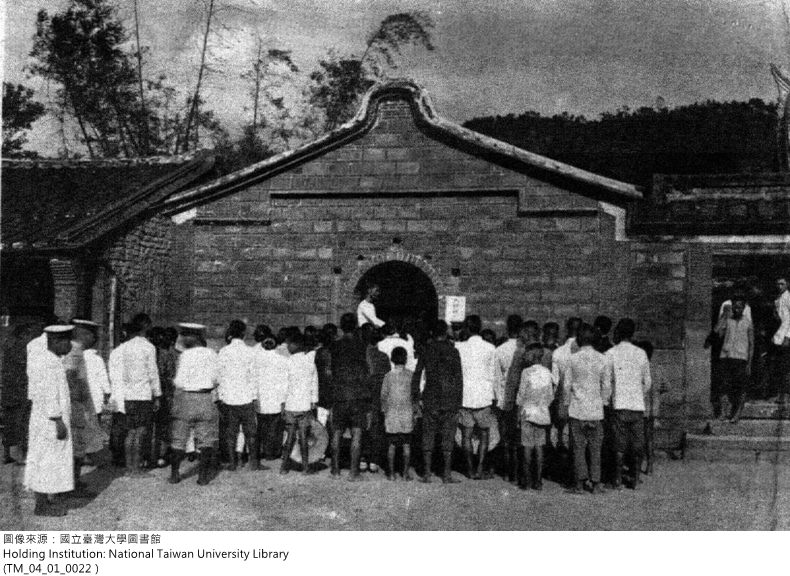

Police inspection of ferryboats (Shilin)

Police quarantine inspection of boats (Taipei)

To prevent cholera, police issued citations to fruit vendors

1.5. The Traditional View of Miasma and Water and Sewage Infrastructure

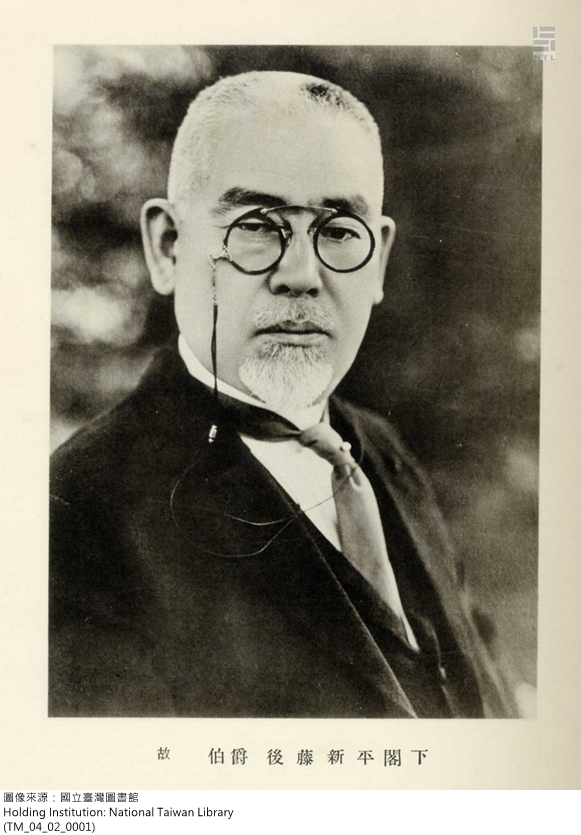

During the great global cholera outbreak in the 19th century, Western medicine had not yet discovered the bacterium that caused cholera and so was still heavily influence by the traditional view of miasma. Sanitation efforts centered on installing a sewage system and a separate clean water supply line. After the Meiji restoration, these two systems were built in Japan to prevent cholera. During the beginning of the Japanese colonial rule, head of the Home Ministry's medical bureau, Gotō Shinpei, was appointed by the Office of the Governor-General as a sanitation consultant, marking the beginning of emphasis on sanitation facilities in Taiwan. In 1896, Gotō recruited William K. Burton (1856-1899) to Taiwan as a sanitation facilities project consultant for the Office of the Governor-General. Burton was responsible for surveying and planning municipal sanitation projects.

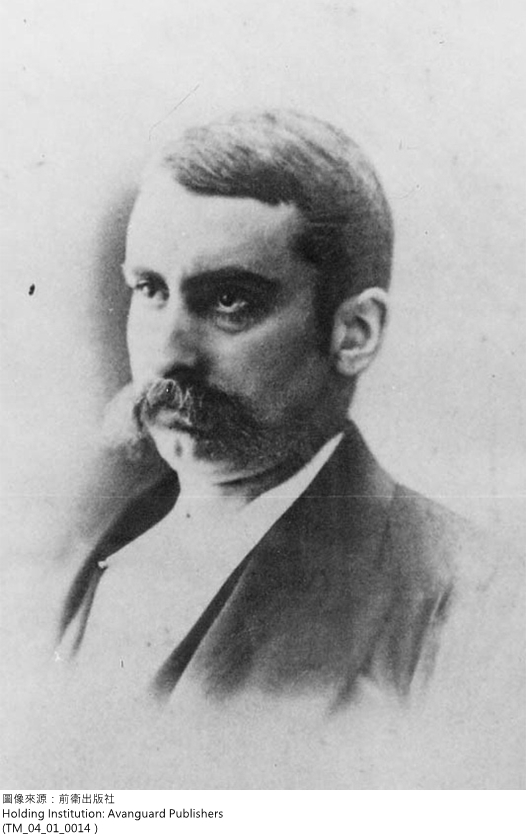

W. K. Burton

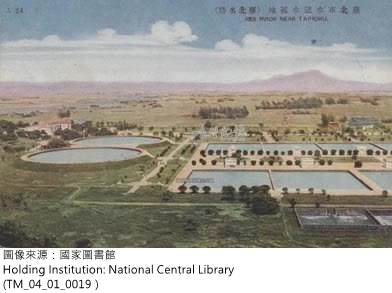

A view of Taipei’s water source

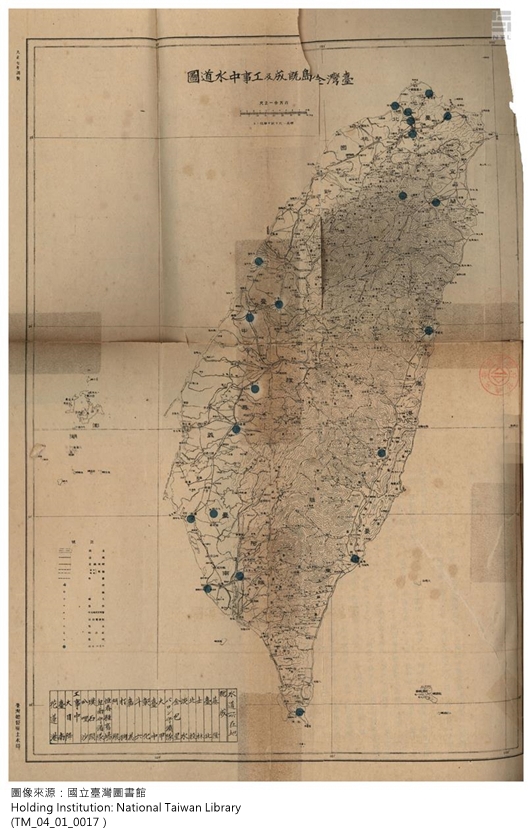

Burton was from Edinburgh, Scotland and was an expert in sanitary engineering. In 1887, he was invited by the Meiji government to act as a consultant engineer for the Sanitary Department of the Home Ministry and a professor of sanitary engineering at Tokyo Imperial University. This was the first professorship in Japan for sanitary engineering. Burton traveled to all major cities in Japan to conduct sanitation surveys and propose water systems and sanitation improvement projects in an effort to prevent cholera. Of particular importance was the water and drainage systems in Tokyo. In 1896, Burton came to Taiwan with his student Hamano Yashirō in a desire to make a professional contribution to Taiwan. Not only did they survey the sanitation of Taipei and the streets and markets where the Chinese lived, they also traveled to Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Singapore to understand conditions where Chinese and foreigners lived together. Because of this, he proposed basic principles of sanitation and was able to plan a comprehensive project that encompassed city planning, buildings, and water and drainage systems. 1898, the Office of the Governor-General announced laws regarding environmental sanitation based on his work. In 1897, Burton was infected with malaria while investigating the origin of Taipei’s water source. Later, he came down with dysentery. In 1899, after completing the Keelung waterworks project, he returned to Tokyo because an old illness had returned. In August of that year he died of a sudden liver infection. The sanitation projects underway were then completed by Hamano Yashirō.

Water system distribution chart (1918)

Hamano Yashirō

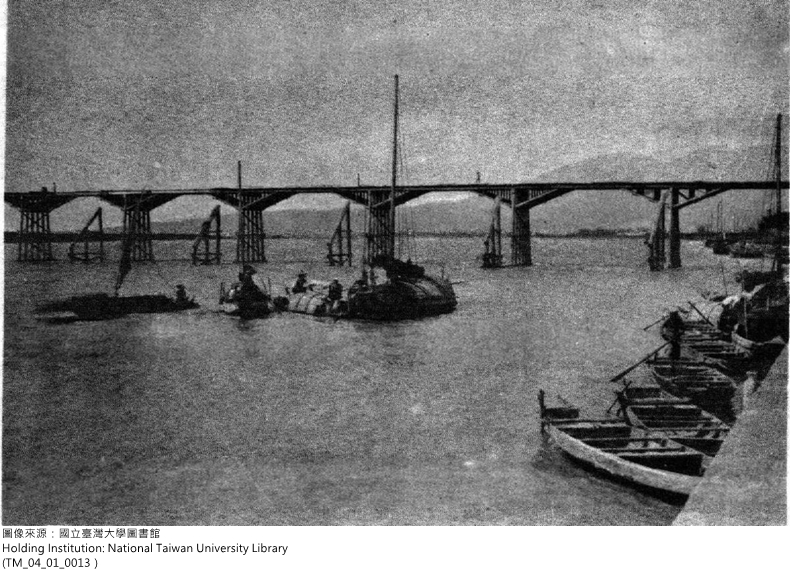

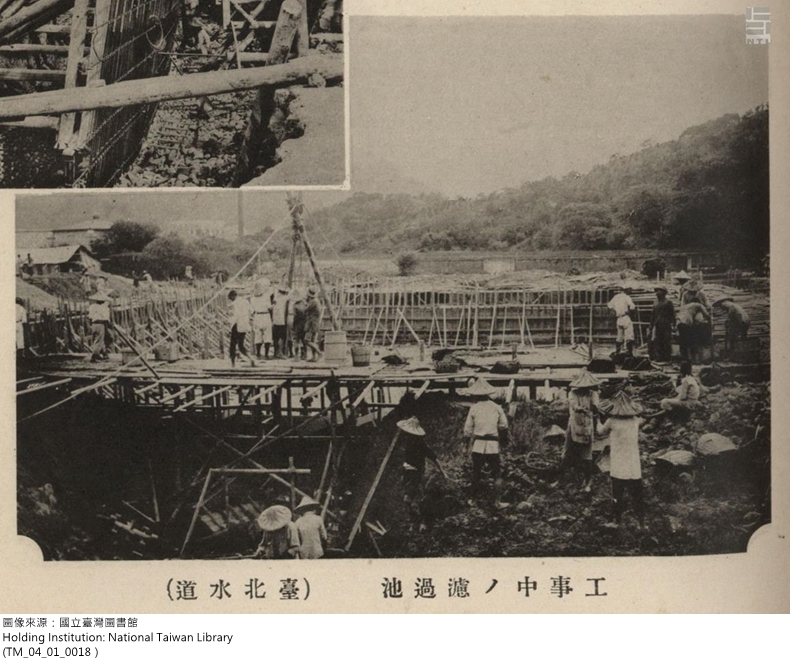

The construction of a water system in Taipei

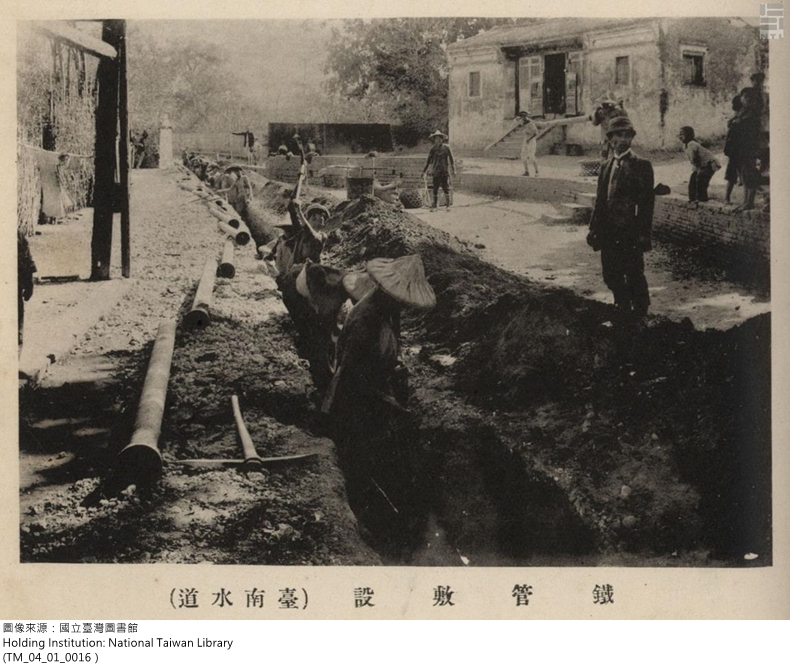

The construction of a water system in Tainan

1.6. The Age of Bacteriology and the Beginning of Disease Prevention

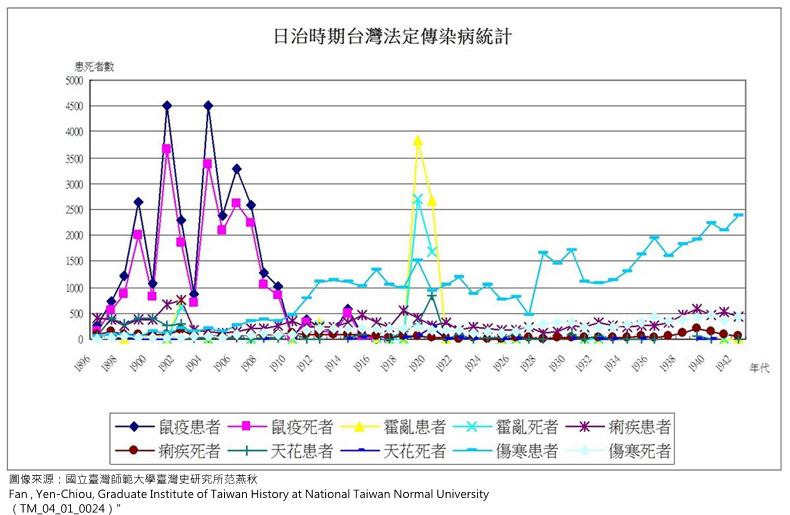

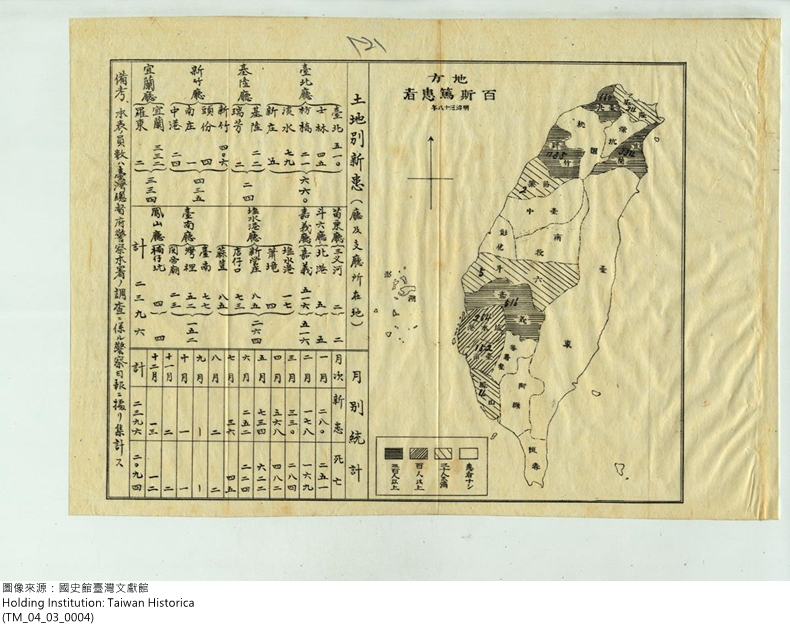

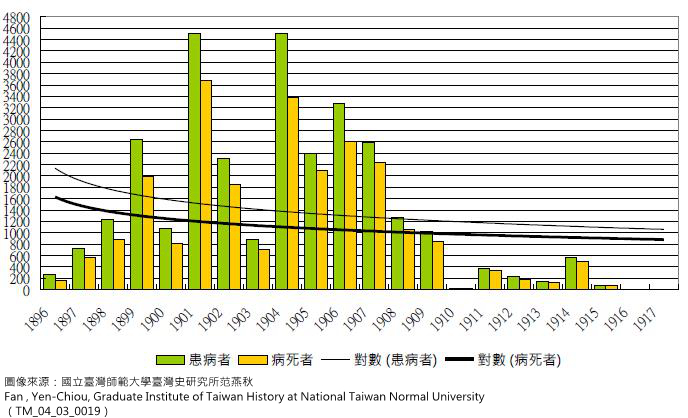

In 1883, German physician Robert Koch (1843-1910) discovered the bacterium vibrio cholera, which marked the beginning of Western medicine’s advent to the age of bacteriology. It also guided the direction of disease prevention, namely to isolate or treat those infected or who seemed to be infected (the carriers) to prevent spread. Other measures included a national announcement and designation of specific communicable diseases, meaning legally designating the concept of communicable diseases to guard against or prevent infection and outbreaks. In October 1896, the Office of the Governor-General issued regulations outlining prevention measures for such disease in Taiwan, including the bubonic plague, smallpox, cholera, typhoid fever, and dysentery. Designated prevention measures included setting up quarantine units, isolating infected persons, disposing of the bodies of those who died from infectious diseases, and stipulating the responsibilities of doctors to inform patients. These were the basis of their prevention efforts. Image 1 shows statistics of legally-designated communicable diseases in colonial Taiwan. It is apparent that the prevention and treatment measures enacted by the Office of the Governor-General were effective for these common diseases. However, to fully understand how such measures brought about the concept of public health, each disease must be addressed individually.

The bacterium vibrio cholerae

Prevention shots for cholera

Testing for cholera

Statistics of communicable diseases in Taiwan during the Japanese Occupation Period

2. Gotō Shinpei and the Establishment of Public Health in the Early Colonial Period

2.1. Facing Challenges of a Tropical Colony: Gotō Shinpei’s Motion

Taiwan was the first modern overseas colony of Japan. It was also a tropical colony. During the invasion in 1895, the Japanese army was stricken with all sorts of infectious diseases, resulting in the loss of much life and resources. This shows that one of the greatest challenges of ruling Taiwan was the issue of tropical diseases. During the colonial period, Japanese control of Taiwan was never solid. This was due to military resistance by the Taiwanese, as well as the ever-present threat to Japanese officials of contracting local diseases and the relatively high death rate of these diseases. In 1898, Gotō Shinpei, in his role as Head of the Civil Affairs Bureau in the Office of the Governor-General, outlined “A New Method for Ruling Taiwan” in which he explored the various difficulties of ruling the island. One of the important items he listed was “malignant epidemics and diseases have not been eliminated.” This shows that overcoming the issues related to communicable diseases became major goal for the government.

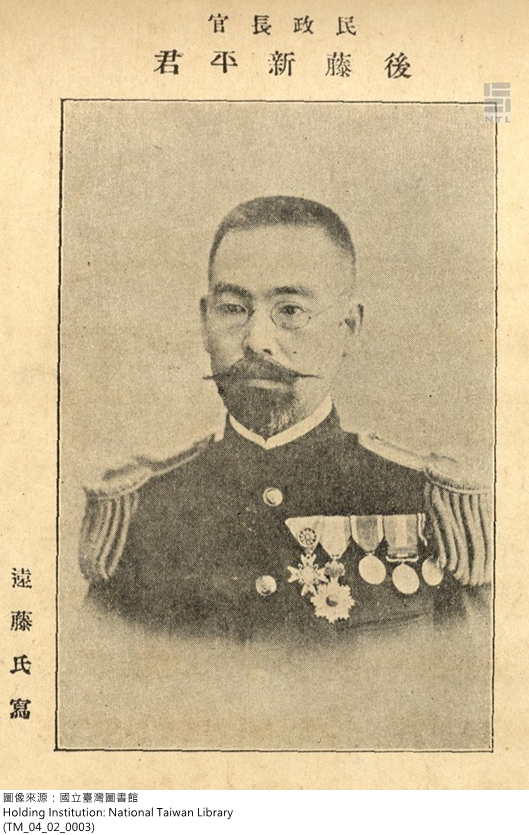

Goto Shimpei: Director of Civil Affairs for the Governor General’s Office of Taiwan

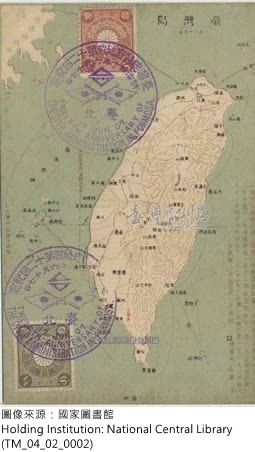

Map of the Island of Taiwan

2.2. Governing through Principles of Biology and the Use of Public Health

Gotō Shinpei (1857-1929) began as a physician and later became a public health administrator. He was also one of the founders of public health in modern Japan. In 1896, as head of the Ministry of Interior’s Medical Bureau, he paid close attention to how the administration in Taiwan dealt with Taiwan opium addicts. He proposed a policy that would gradually ban opium in Taiwan, which was adopted by the central government in Japan. Because of this, he was asked by the Office of the Governor-General in Taiwan to be a public health consultant and to be responsible for generating an opium system and health system for Taiwan. In April 1898, Kodama Gentarō was selected as the new Governor-General, and he assigned Gotō to be the head of civilian affairs within the Office of the Governor-General, with control of all administrative duties for the colony. Gotō faced many difficult issues regarding the Taiwan colony. He adopted, in response to these, the idea of governing through principles of biology, or what may be termed scientific colonial policies. The unique features of governing through principles of biology are an emphasis on scientific surveys, the use of talented individuals, and measures calculated to produce gradual advancement. The analogy that Gotō Shinpei gave was a porgy’s eyes grow on either side of its head, whereas a flounder’s eyes grow on one side of its head—one cannot replace a porgy’s eyes with those of a flounder. This means, the customs and structure of a society is something that has formed over a long time in response to various needs. The reasons for its existence cannot be changed on a whim. As such, the urgent matter in governing Taiwan is to conduct scientific inquiries into the old customs and social structure in Taiwan and then adopt policies that conform to the conditions of the people. It is not proper to rashly transplant Japan’s legal system onto the system already in Taiwan. Otherwise, doing so is nothing more than civilized tyranny. Based on his viewpoint, the way to overcome diseases common to Taiwan was to establish a modern sanitation system, to use science and medicine to investigate and research these illnesses, and only then to implement effective prevention measures based on Taiwanese social customs.

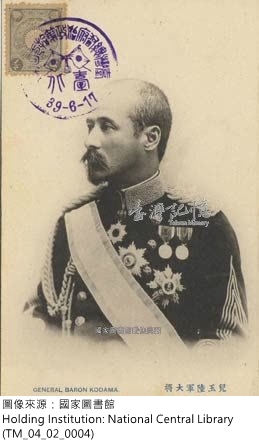

Kodama Gentarō, Governor-General of Taiwan

Gotō Shinpei, Head of Civil Affairs in the Office of the Governor-General

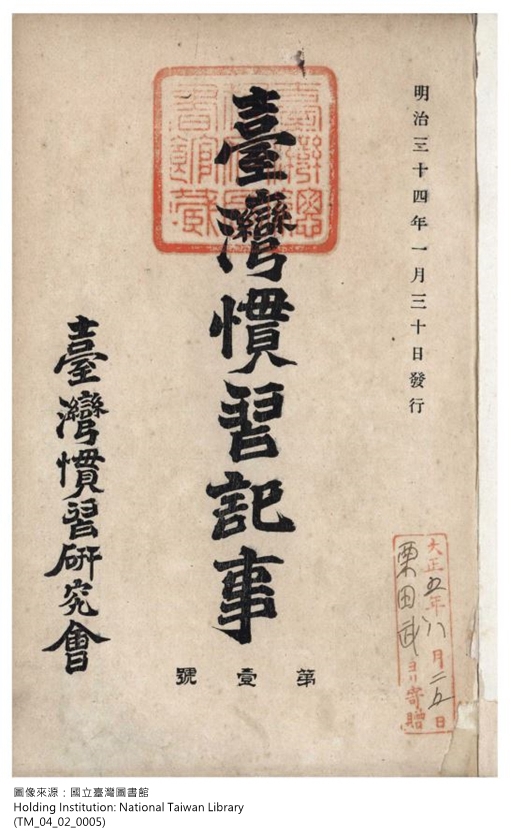

Cover of the Records of Taiwanese Customs

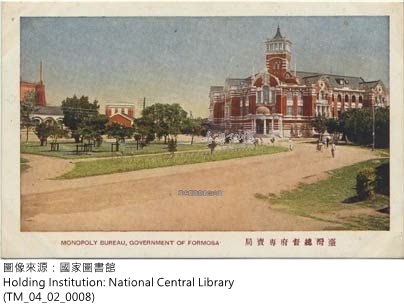

2.3. The Policy of Gradually Banning Opium and the Financial Independence of the Office of the Governor-General

In the beginning of colonial rule, one of the first health policies aimed at Taiwanese was the policy of gradually banning opium proposed by Gotō Shinpei. This was in line with his strategy of governing through principles of biology. At the time, most Japanese officials held that opium should be strictly banned in Taiwan. However, Gotō’s proposal won out in the end because it allowed for the government to monopolize opium sales as a means of income, whereas strictly banning opium would cause resistance by the Taiwanese people. The opium policy outlined by Gotō had three main points: first, opium would be only sold by the Office of the Governor-General through designated pharmacies throughout Taiwan; second, only addicts diagnosed by a doctor could be issued an Opium User License (also known as Opium User Special License), which was needed to purchase opium to smoke; third, a high tax on opium would be assessed which would result in a large revenue for the Office of the Governor-General. This enabled the colony of Taiwan to go from being in debt to financial independence in 1905.

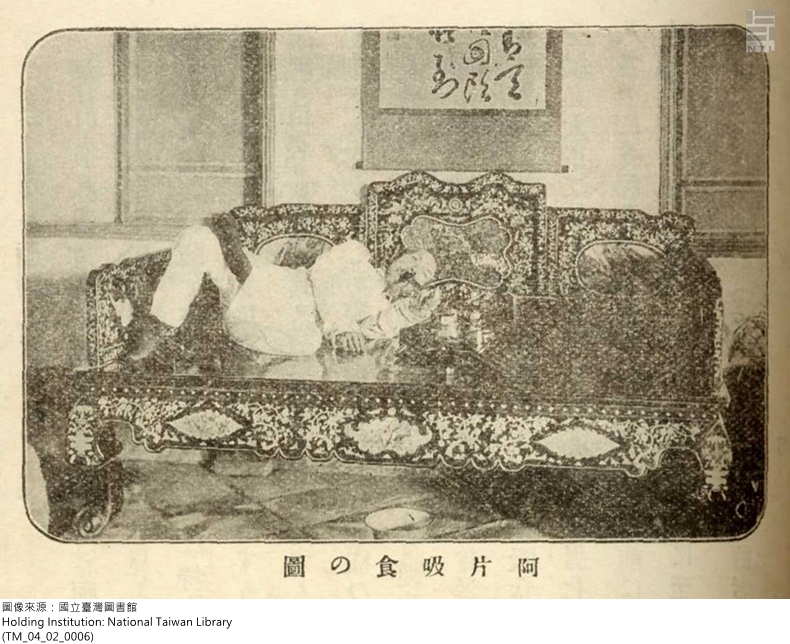

Taiwanese taking opium

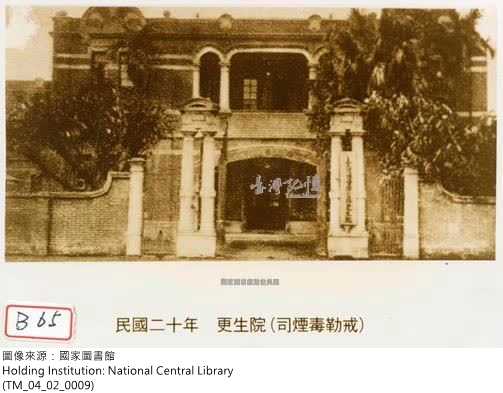

After that point, there was no longer a need for financial reliance on Japan’s central government. After this policy went into effect, opium users in Taiwan went from more than 160,000 in 1900 to only 20,000 in 1928. While the number of users gradually decreased, it was not because the gradual prohibition policy was efficacious but rather because of certain background factors. These factors include the natural death of opium smokers, modern education on the harm of opium smoking in colonial Taiwan, and the conscious awakening of the Taiwanese as a people in the 1920s. When the anticolonial movement started and under the influence of the international sanitation movement, the Taiwanese began to oppose the colonial government’s right to sell opium. In 1930, the Taiwanese People’s Party spearheaded an anti-special rights on opium movement, causing the Office of the Governor-General to revise its policies on opium and to set up Taiwan Renewal Centers. Medical doctor

Du Cong-ming was placed in charge of the rehabilitation efforts. This is how opium entered the gradual prohibition stage.

Du Cong-ming

Du Cong-ming, Doctor of Medicine

The Taipei Renewal Center

The Monopoly Bureau of the Governor-General Office

2.4. Modern Health System and the Prevention and Treatment of Communicable Diseases

In 1896, Gotō Shinpei’s original plan for a modern health system included not only sanitation laws but also the selection of outstanding professionals from Japan to come to Taiwan to assist in the effort. Laws included the promulgation of prevention protocols for infectious diseases and the establishment hospitals and a public health system. Talented people included William K. Burton, a lecturer in the medical department at Tokyo University who came to Taiwan to plan a sanitation system, and Yamaguchi Hidetaka, who was appointed as the director of the Taipei Hospital. In early 1898, after Gotō was made the head of civil affairs in the Office of the Governor-General, he reorganized the modern health system with the goal of preventing and curing communicable diseases.A health system is comprised of two complementary modern organizations: first is a modern medical system; the other is a health administrative organization. The establishment of a modern medical system during the colonial era was first done by setting up hospitals and a public health system. Next, was to increase the number of medical professionals in the colony and to train local Taiwanese doctors. Public hospitals established before the colonial era were put under the direct jurisdiction of the Office of the Governor-General in 1898 and were renamed government hospitals. These became modern hospitals in each of the major cities. In 1896, a public health system was set up with public health centers established around the island to provide medical treatment and promote public health. In April 1897, the director of the Taipei Hospital, Yamaguchi Hidetaka, set up in the hospital a Medical Learning Center for Locals. In March 1899, it was renamed the Taiwan Medical School of the Office of Governor-General and was a training ground for developing doctors in modern medicine among the Taiwanese.

Regulations for a Taiwan medical license

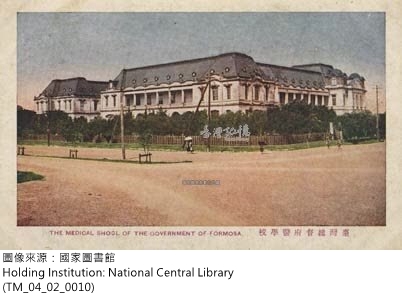

Taiwan Medical School of the Office of the Governor-General

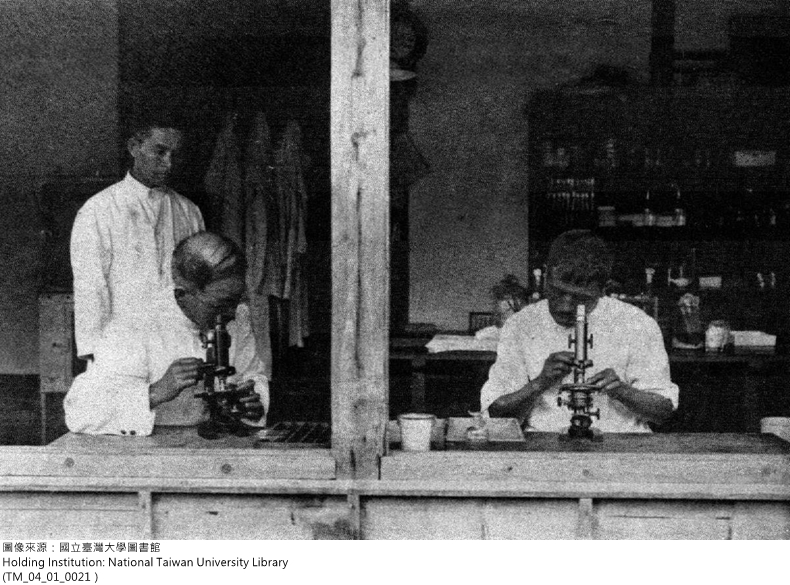

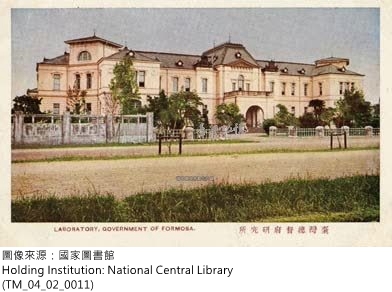

Taiwan Research Center of the Office of the Governor-General

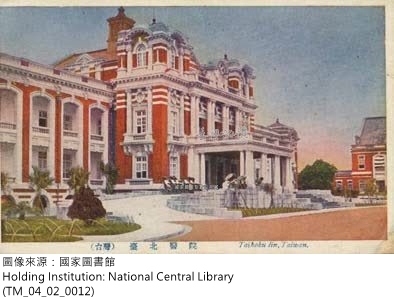

The Taipei Hospital of the Office of the Governor-General

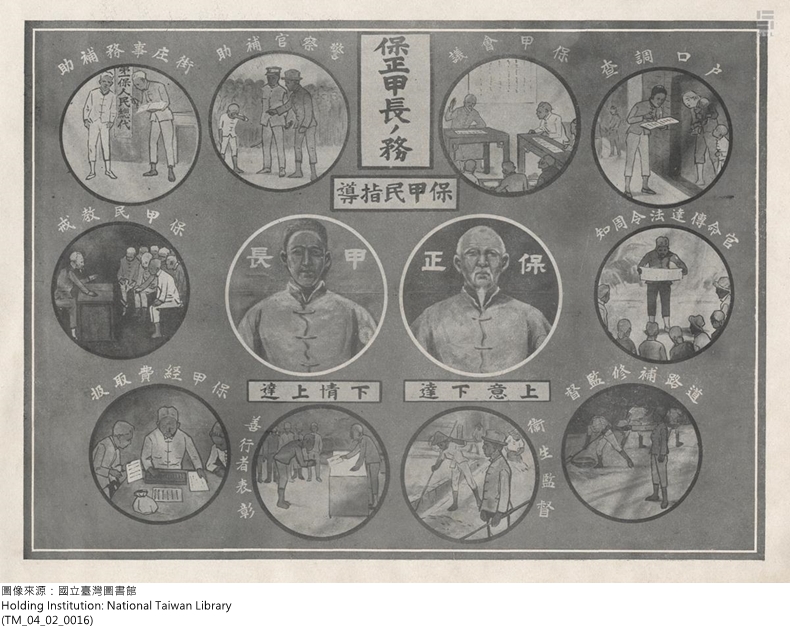

At the same time, the Committee to Investigate Communicable Diseases and Local Diseases was also established in 1899 to investigate local diseases in Taiwan. In 1906, a medical research institution known as Taiwan Research Center of the Office of Governor-General was set up. In other areas, the Regulations for the Licensing of Taiwan Doctors was announced in 1901 in an effort to encourage traditional Taiwanese medical practices and to provide a qualifying exam for Chinese medicine. However, this was only held one time so as to limit the development of Chinese medicine. That is to say, modern medicine was promoted and expanded while traditional Chinese medicine was suppressed so that a modern medicine system could be firmly established.As for a health administrative organization, health administration at the time fell under the jurisdiction of the Japanese police. In Taiwan, the Hoko system (a traditional security system based on households; also called the baojia system in Chinese) was utilized. In 1898, the Office of the Governor-General adopted the Hoko system and combined it with the law enforcement system. This was done in an attempt to reduce administration costs and to continue old ways of doing things. This basic level of administration reached all areas of Taiwan, making it an inexpensive but mandatory way of handling basic administrative operations. At the time the police and Hoko officials were in charge of public health and also basic administrative duties. That is to say, the police not only went after criminals but bacteria as well!

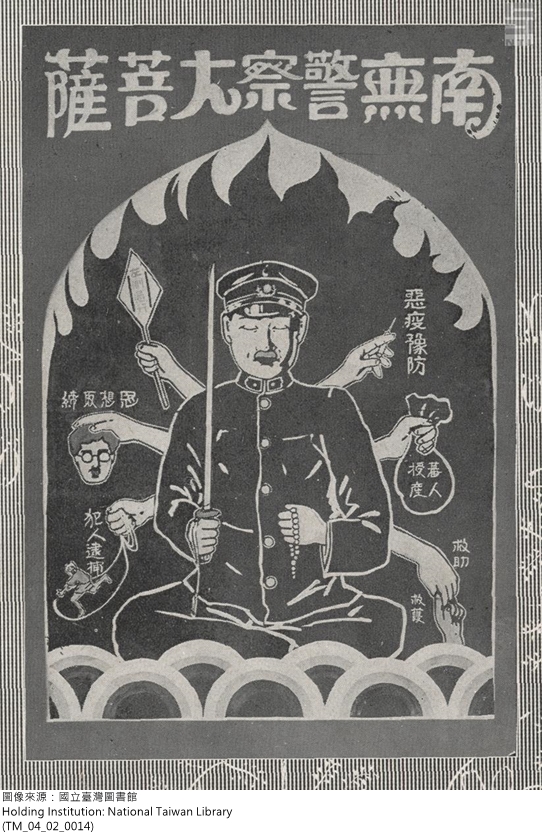

Figure of a health officer in the propaganda of the colonial government

Baojia organization helps in the prevention of infectious diseases

The duties of Hoko chiefs

2.5. Establishing Public Health and Solidifying Governance over Taiwan

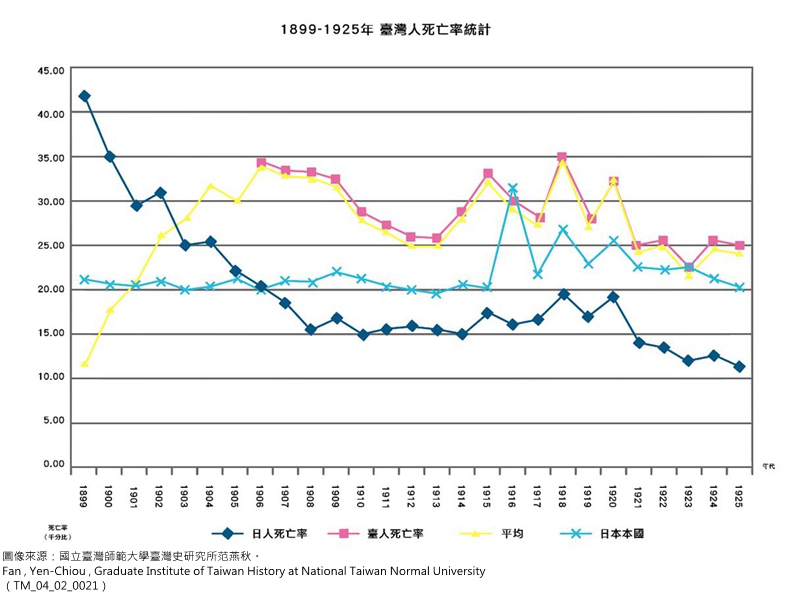

In 1901, Japanese sanitation engineer Takagi Tomoe was invited to come to Taiwan and take up the post of head of the Department of Health in the Office of the Governor-General. His primary duties were to manage the health administration in Taiwan and to begin the work of preventing diseases, especially that of the bubonic plague. In the 1910s, the major communicable diseases in Taiwan, such as cholera and the plague, were gradually controlled. Sanitation greatly improved in cities. After 1905, the death rate of Japanese in Taiwan was not only lower than that of the Taiwanese, but also of Japanese still in Japan. This shows that the Japanese in the colony received excellent healthcare. This result proved to strengthen the colonial government, as well as benefit the development of colonial politics and the economy. At the same time, it also laid the foundation for the development of public health in Taiwan and aided in the establishment of a modern society.

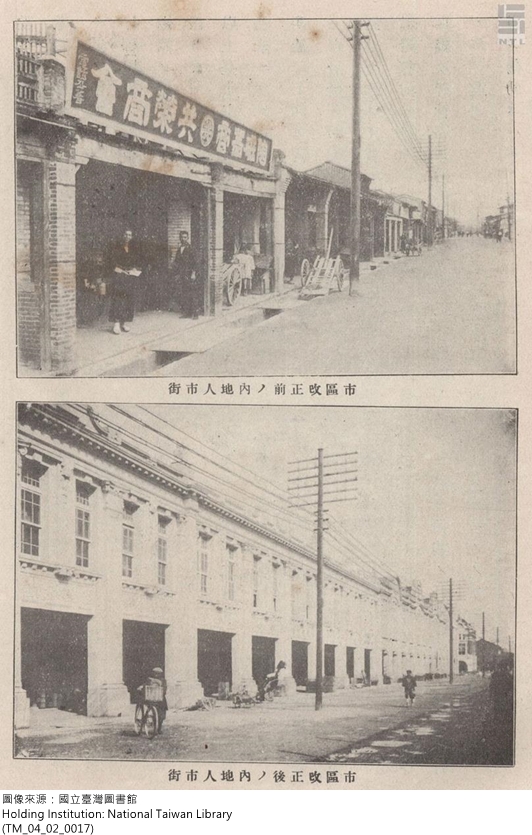

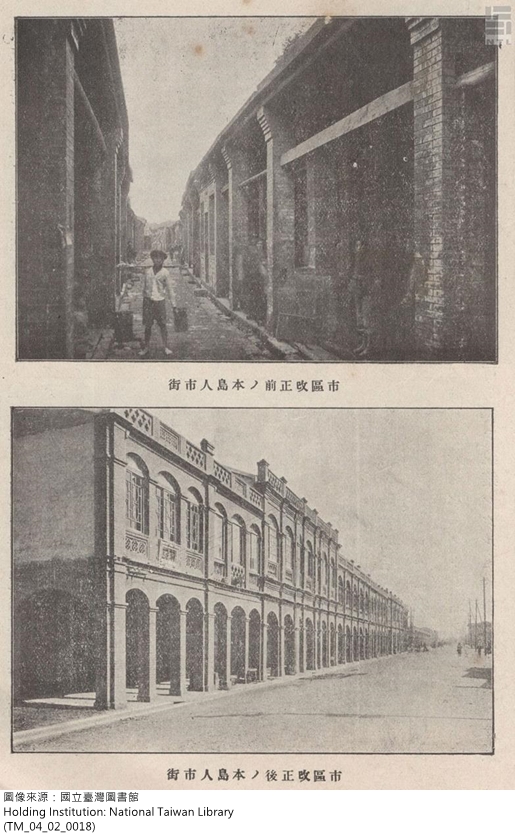

Public health works: A Japanese street before and after renovation

Public health works: A Taiwanese street before and after renovation

Takagi Tomoe

Takagi Tomoe, Head of the Department of Health in the Office of the Governor-General

Police doctors go for a checkup

Population mortality statistics in Taiwan between 1899 and 1925

3. The Prevention and Treatment of the Bubonic Plague in Early Colonial Taiwan

3.1. Black Death in the Early Colonial Period

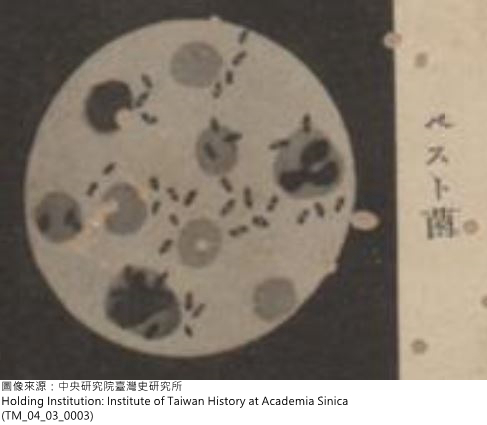

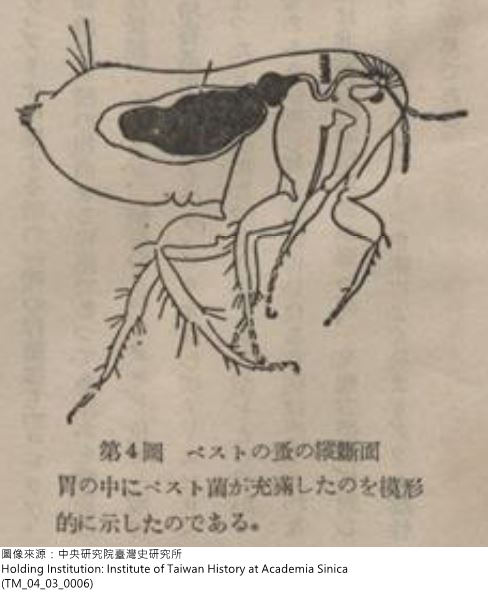

The bubonic plague exists in mice and fleas and can infect both man and beast. It is often transmitted to humans and mice through fleas. In the Taiwanese dialect it is called the “mouse disease”; in Japanese it is called “pesto” from the English “pest.” Symptoms can vary depending on the type of plague contracted. Thus, the plague is further divided in to the bubonic plagues (which affects the lymph nodes), the pneumonic plague (which affects the lungs), and the septicemic plague (which affects the blood). Several outbreaks of the plague have occurred in history, such as the Black Plague in 14th century Europe which killed millions of people and caused a sharp population decline. The name “black plague” comes from the fact that those infected start to get red splotches on their skin, their face starts to swell, and then black splotches start to cover their body when death is imminent. Actually, these are the classic symptoms of the septicemic plague. In the 1910s, northeast China had a major outbreak of the plague. It was a pneumonic plague transmitted through the airways. In 1896, the bubonic plague, which causes the lymph nodes to swell, broke out in Taiwan during the beginning of Japanese rule.

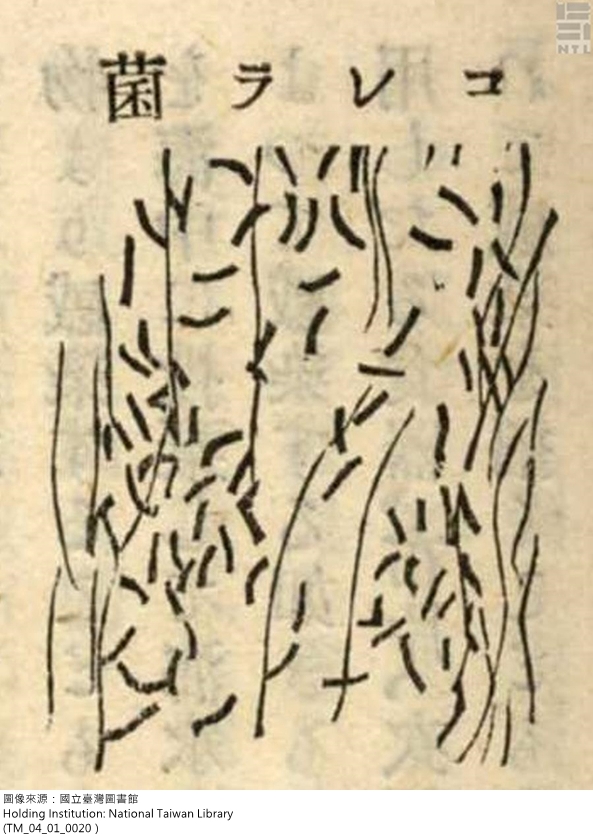

Rattus Norvegicus: A kind of bacteria carried by rats

Rattus Norvegicus: A kind of bacteria carried by rats

3.2. The New Discovery in Bacteriology and the Bubonic Plague Follow Japanese Colonists to Taiwan

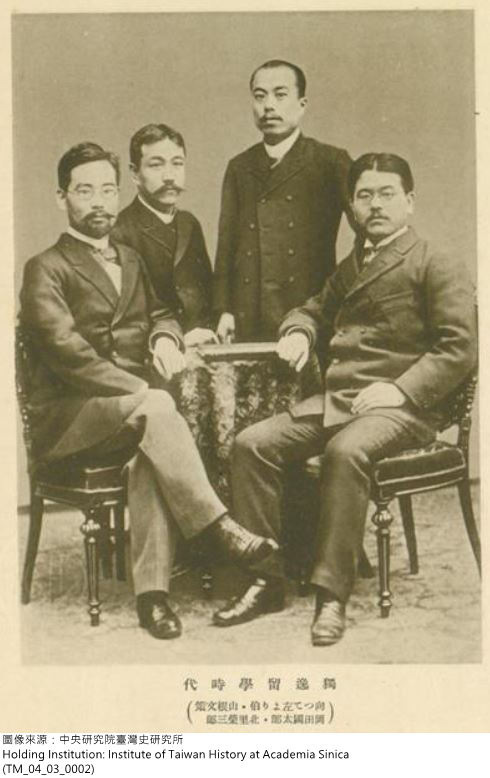

An outbreak of the bubonic plague occurred in southern China at the end of the 19th century. In 1894, it spread to Britain-ruled Hong Kong and garnered the attention of scientists across the world. Two bacteriologist—A. Yersin from France and Kitasato Shibasaburō from Japan—traveled to Hong Kong to investigate the cause of the outbreak. Both independently found that the cause was the yersinia pestis, which was found on the bodies of those infected. This was an important discovery in bacteriology and for modern medical history. It symbolized the advent of the age of laboratory medicine.

Yersinia pestis

Kitasato Shibasaburō

Kitasato Shibasaburō (far right)

Not long after the outbreak of the plague in Hong Kong in 1894, it made its way to Taiwan due to the frequent ships that traveled back and forth. In 1896, the Office of the Governor-General first discovered cases of the plague in the streets of Taipei. Later it was discovered that Tainan had already had cases there. In 1897, the plague made its way to central Taiwan. Thus, a three-pronged epidemic of the plague began ravaging northern, central, and southern Taiwan. The disease quickly spread to all major cities in the west of the island. The colonial government attempted to stop its spread by investigating cases and enacting quarantine measures, as outlined in its regulations for preventing infectious diseases. However, this cause panic in the Taiwanese, as they viewed such actions as tyrannical whims by the new government. Various methods were used to avoid and to resist quarantine. This outbreak of the plague in Taiwan not only caused major economic losses but also was a threat to the stability of colonial rule. The colonial government viewed the black plague and the rebel bandits that fought against the government as being on the same threat level. From this one can see the danger posed by the plague.

A map of Japanese soldiers infected with the plague in Taiwan in 1905

3.3. Takagi Tomoe’s National Prevention Plan and the Battle between Men and Mice

At the end of the 19th century, medical experts had discovered the cause of the bubonic plague, but were unclear on how it spread. In December 1896, the colonial government attempted to understand how it was transmitted and thus invited two professors from the Imperial University of Tokyo, Dr. Ogata Masanori and Dr. Yamagiwa Katsusaburō, to come to Taiwan. They demonstrated that the fleas on the mice and rats were the true germ carriers. The results of this inquiry explained how the disease spread and what effective measures for prevention were.

Tokyo Imperial University bacteriologist

Ogata Masanori

A flea infected with the plague

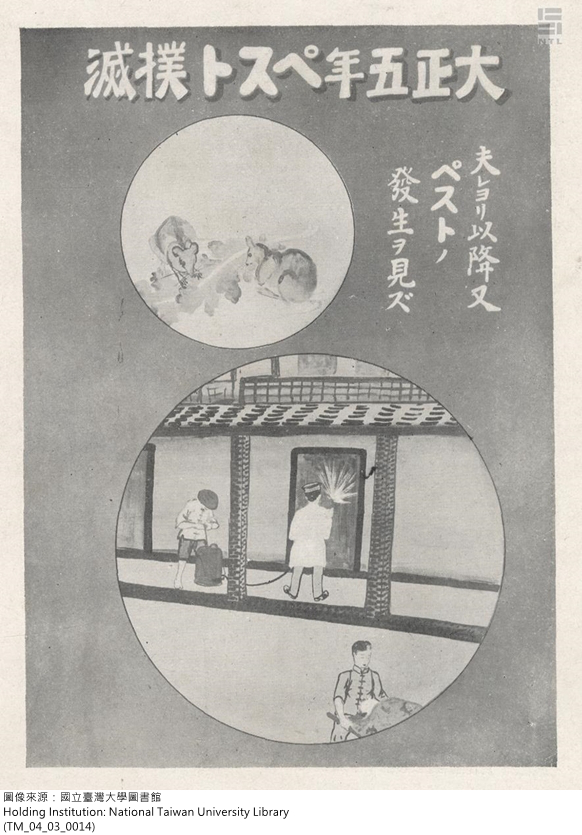

In 1901, the plague was particularly serious throughout all of Taiwan. More than 3,000 people had died from it. The Office of the Governor-General decided to begin prevention efforts. In 1902, Japanese epidemic prevention expert Takagi Tomoe was invited to Taiwan to head up these efforts. His approach was to eradicate mice. Prevention measures included teaching the people how to catch mice, such as mouse traps or rat poison; mobilizing large-scale social participation to catch mice, either through monetary incentives for catching mice or through compulsory fines via the Hoko system for households not catching them. In addition, city streets were being rezoned or houses that where infections occurred were being torn down, and environmental cleanliness was rigorously enforced (such as spraying disinfectant). Due to the development of modern immunology, preventative immunizations were given in places where the plague broke out in an attempt to increase the immune systems of the public. This also was a source of fear for the people though.

Japanese plague prevention expert

Takagi Tomoe

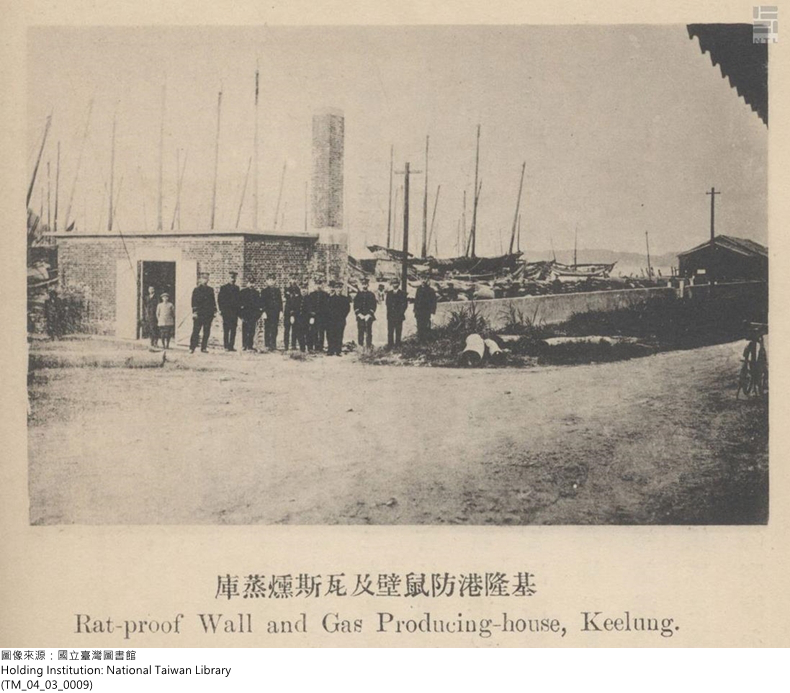

Rodent-proof wall in Keelung

At the same time, to prevent the plague from entering Taiwan, seaport quarantine was made more rigid. In 1899, the Office of the Governor-General announced the Regulations for Quarantine at Taiwan Seaports. To comply with the regulations on preventing communicable diseases, each port inspected ships for such diseases. Also, to prevent the plague from being transmitted from overseas, Keelung, Tamsui, and Kaohsiung set up rodent-proof walls, used gas and smoke, etc. to rid the port cities of mice.

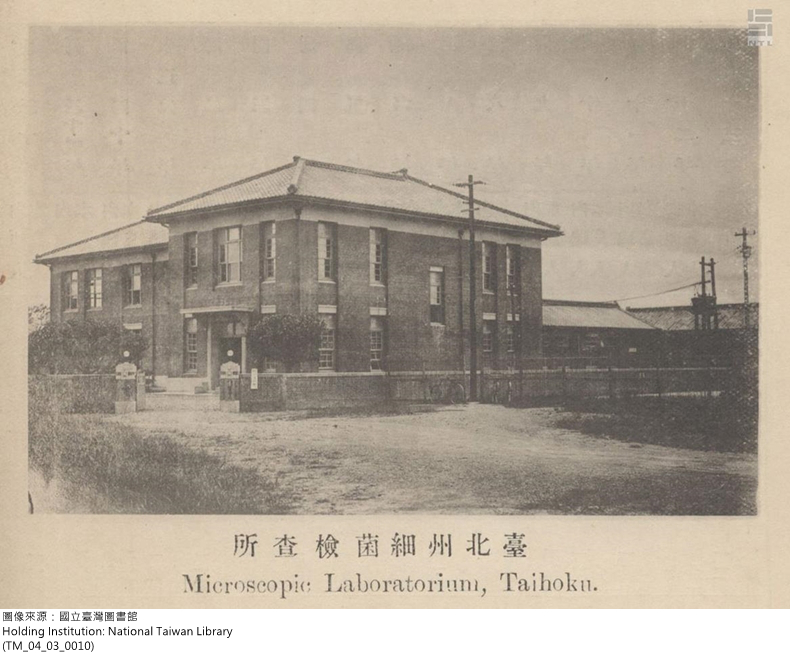

A bacteria inspection center in Taipei

Inspection center in Keelung

3.4. Bubonic Plague Prevention Is Integrated into Taiwan’s Society: Major Cleaning by Households and Daily Sanitation

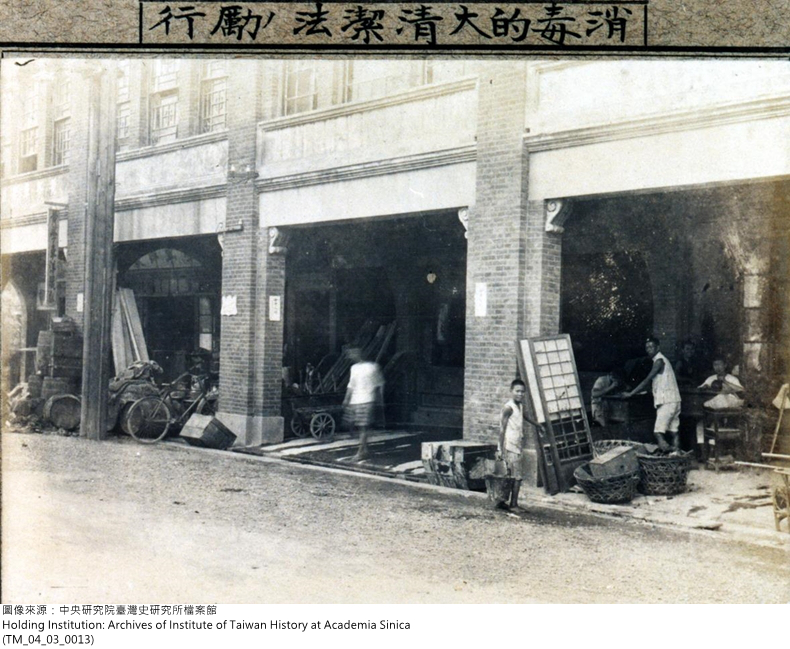

After the spread of the plague was discovered throughout Taiwan in the early colonial period, the Office of the Governor-General issued an order to local governments to disinfect and clean their cities or to hold impromptu major cleaning. Yet since the plague happened every year, a major cleaning in each area became a regular event. In 1905, the Office of the Governor-General announced Regulations for Compliance with the Major Cleaning Law, which stipulated that the heads of local governments must schedule a major cleaning day during the spring and fall of each year and specify the location and the main objectives. In addition, police officers, Hoko chiefs, and other officials were required to meticulously inspect each household to ensure effectiveness. During this process, constables would take the inspectors and police to inspect each household and affix a notice of “clean” or “not clean”; those who did not pass were required to keep cleaning until they passed. This biannual major cleaning gradually became something the Hoko officials did of their own accord, transforming it into a part of people’s daily life.

A traditional house that contracted the plague in the Chiayi region

The Taipei government carried out a major household cleaning in 1919

Catching mice in Puzaijiao, Chiayi in 1914 during the plague

A propaganda poster of police exterminating the plague

3.5. Taiwan Society’s Silent Resistance and Adaptation

In the beginning of the 20th century, Western medicine still lacked effective treatment medicine for the plague. So local prevention efforts were only centered on stopping the spread of the disease through eliminating mice. However, the plague epidemic caused tense relations between the Japanese and Taiwanese. For Taiwanese, life was disrupted regardless—either through contracting the plague or through the prevention measures of the colonial officials. Local prevention measures included police visits to homes to find those ill with the plague, sending infected persons to be quarantined and treated, burning the infected person’s clothing, intensifying cleaning efforts of the infected person’s house and surrounding area, and sealing off the home of the infected person for seven days with no ingress or egress. For those areas where the plague was more serious, an infected person’s house would be sealed off for twenty days, or the infected person’s home would be demolished and burned. These measures created a great deal of fear in the Taiwanese, causing some to avoid inspections and hide those infected.

Chiayi quarantine hospital

When the plague was spreading in Taiwan, the initial reaction of the people was to rely on their folk religion and pray to the gods for protection. Later, the local gentry thought it prudent to invite the Chinese medicine doctors to treat the people. It can be seen that the local gentry’s tradition of aiding society turned into actions that led to the promotion of public health. At the same time, Chinese medicine doctors actively participated in the prevention efforts. This proved to mitigate the resistance felt by the Taiwanese toward the prevention measures. In the end, prevention was an amalgam of effort by those in the new and old societies.

Huang, Yu-jie: a practitioner of Chinese medicine

Beigang quarantine hospital

Channghua quarantine house

3.6. The Bubonic Plague Gives Birth to Public Health in Taiwan

In the early colonial period, the plague epidemic in Taiwan lasted more than twenty years. It was not until 1918 that it was suppressed. As the work of prevention continued, it gave rise to the formation of public health in Taiwan. The reason why the large-scale epidemic could be suppressed was not only due to the effective measures implemented by the government, but also the participation of local businessmen, gentry, and Chinese medicine doctors. The labor and united efforts of the Hoko officials and other abled-bodied men were also critical in achieving these results. Clearly, the end of the epidemic in early colonial Taiwan was due to a concerted effort by many aspects of government and society, as well as a collaboration between the new and old cultures.

Statistical table for the deaths and the victims of plague

4. The Prevention and Treatment of Malaria in Taiwan and Tropical Health

4.1. Another Local Disease: Malaria

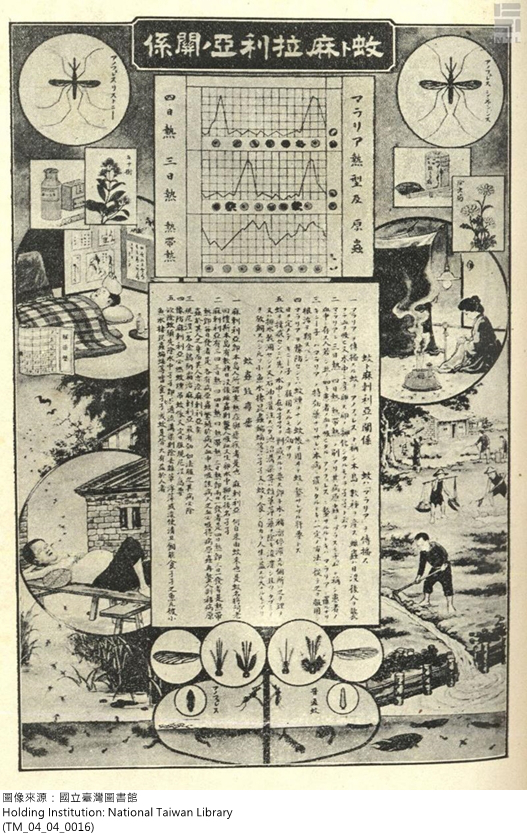

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by the malaria parasite, or plasmodium. It is often found in tropical and subtropical areas. As Taiwan is located in the subtropics, it was in earlier times a place where malaria ran rampant. The main symptoms of malaria are intermittent or cyclical chills or shivers, fevers, and sweating. Because of this, Taiwanese called it the “shivering fever.” In Chinese other common names were: the shakes, chills and fever devil, and the chills and fever illness. In Japanese it was called malaliya based on the English pronunciation, which came from the Italian mala aria meaning “noxious air.” It may also be referred to as miasma, bad air, or even marsh fever according to some books—because it often is found in marshy areas. Local gazetters from the Ming and Qing dynasties designated Taiwan as the “land of miasma” because of the prevelance of malaria there. In 1895, when the Japanese army was invading Taiwan, it lost most of its strength due to soldiers coming down with malaria. Yet they did not understand how it was contracted. They called it the “Taiwan fever.” However, they did know that quinine was effective as a means of prevention and treatment.

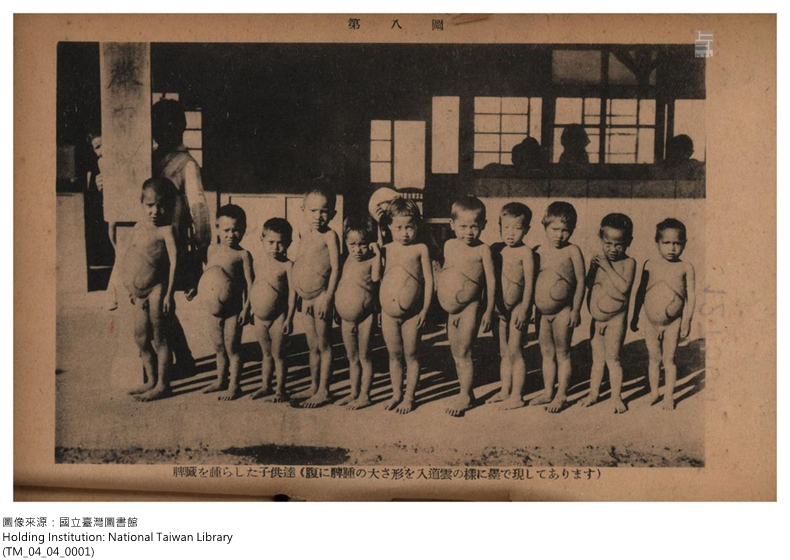

Splenomegaly caused by Malaria

Splenomegaly caused by Malaria

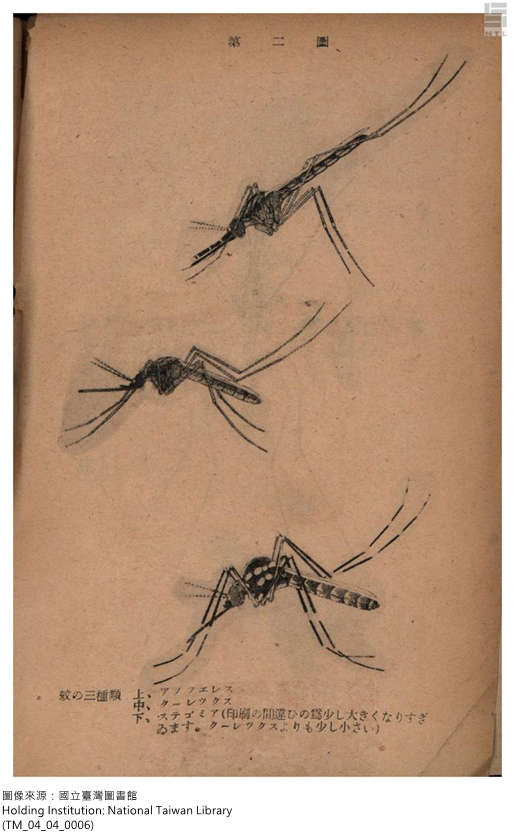

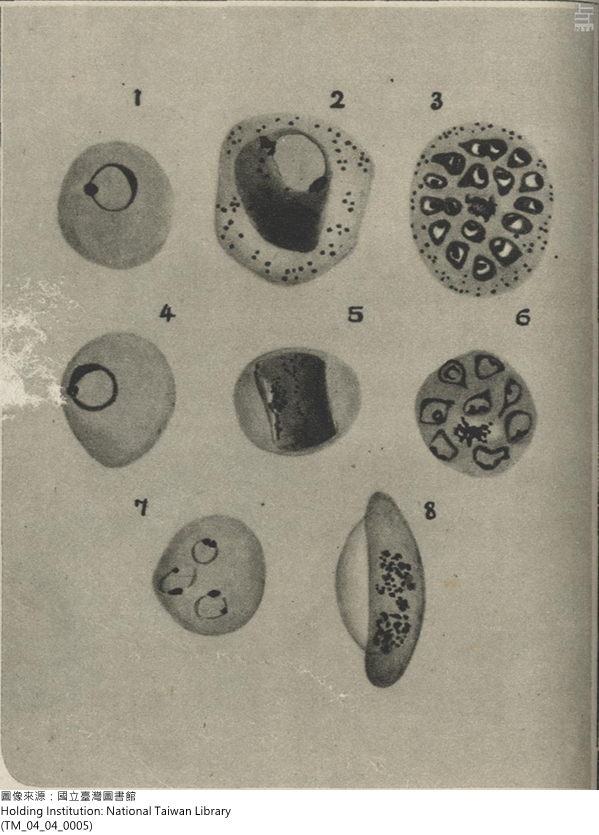

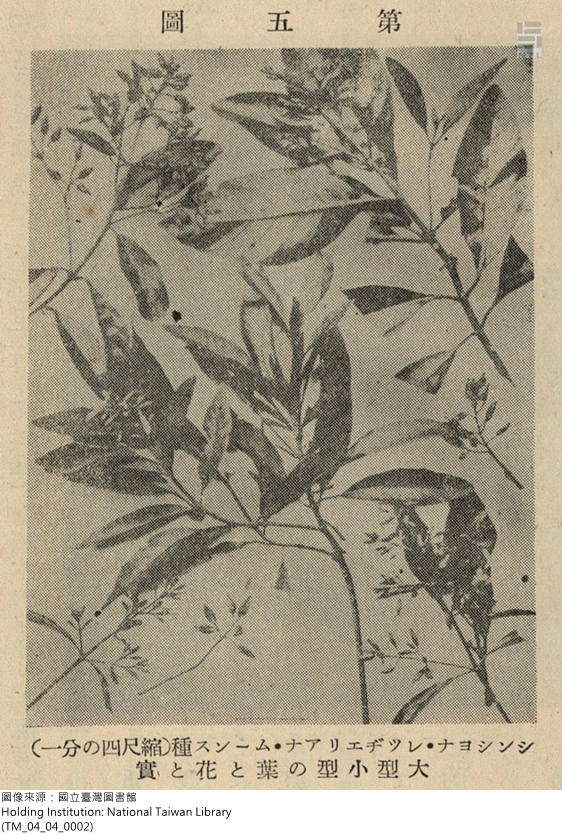

4.2. Research Breakthroughs on Malaria in the Early 20th Century and Tropical Medicine

Before the 19th century, societies in both the East and West believed that miasma was the cause of malaria. In 1880, French army physician Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran discovered that the red blood cells of people infected with malaria contained parasites. This proved that the true cause of malaria was plasmodium. In 1897, British medical doctor Ronald Ross proposed that mosquitoes were the medium by which malaria was transmitted. He was able to prove his hypothesis by showing the malarial mosquito (anopheles) was the main transmitter, opening the way for effective malaria prevention in medicine. This was also a major breakthrough in tropical medicine research in the West. Because of the development of tropical medicine in the West, the Office of the Governor-General also began researching malaria in Taiwan. In 1899, it organized a Committee to Investigate Communicable Diseases and Local Diseases in Taiwan. The investigation lead to a clearer view of where malaria was spreading. From 1901 to 1903, Japanese scholars discovered seven different malarial mosquitoes and thus established a firm foundation on which malaria in Taiwan could continue to be researched. With regard to medical treatment for malaria, the earliest known medicine was made from the bark of the cinchona tree that grows in the mountains of South America. During the mid 17th century, Europeans brought cinchona bark back to Europe. In 1820, a French chemist successfully extracted quinine from cinchona bark, which became the go-to for malaria treatment. Before the 1920s, quinine was the primary medicine available for malaria.

Seedlings of the cinchona tree

Cinchona tree bark

Three types of malarial mosquitoes

The malaria parasite

Cinchona tree

4.3. Malaria Prevention and the Anti-Mosquito Experiment of the Japanese Army in Taiwan

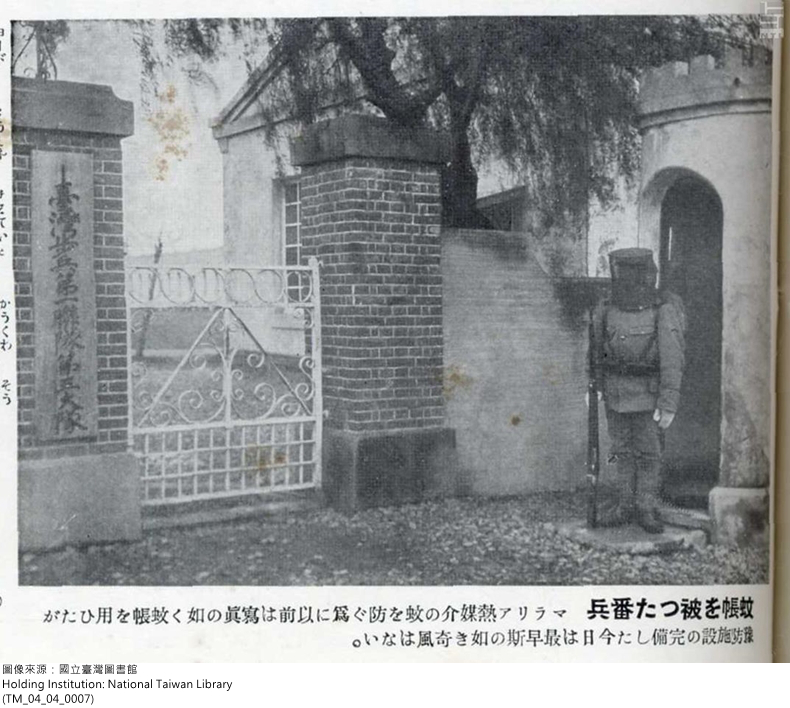

During the invasion of Taiwan, malaria ravaged the Japanese army. It continued to be the most serious tropical health issue for Japanese after they took control of the island. Health statistics for the Japanese army in the early colonial period show that as of 1900, each year the Japanese lost at least half of its strength and the previous two years the loss was as more than 90%. The primary cause of this was malaria. As military strength is the key backup force for consolidating control of a colony, maintaining the health of the army became a primary concern for the colonial government. Because of this, malaria prevention in Taiwan began with the Japanese army. Between 1901 and 1902, malaria prevention experiments were conducted on the army bases, consisting primarily of mosquito nets, screens, and head nets. The aim of avoiding being bitten by the malaria mosquitos proved to be effective. From pictures taken at the time, one can see Japanese soldiers standing guard with mosquito head nets on. They look quite comical. These head nets worn in the summer were special-issue items; not everyone could obtain one. Newspaper advertisements at the time claimed these head nets could stop poisonous insects, were a must for traveling, and were the best gift you could give a soldier.

A soldier wearing a mosquito net

Malaria Distribution Map

4.4. The Expansion of Malaria Prevention: Methods for Humans and for Mosquitos

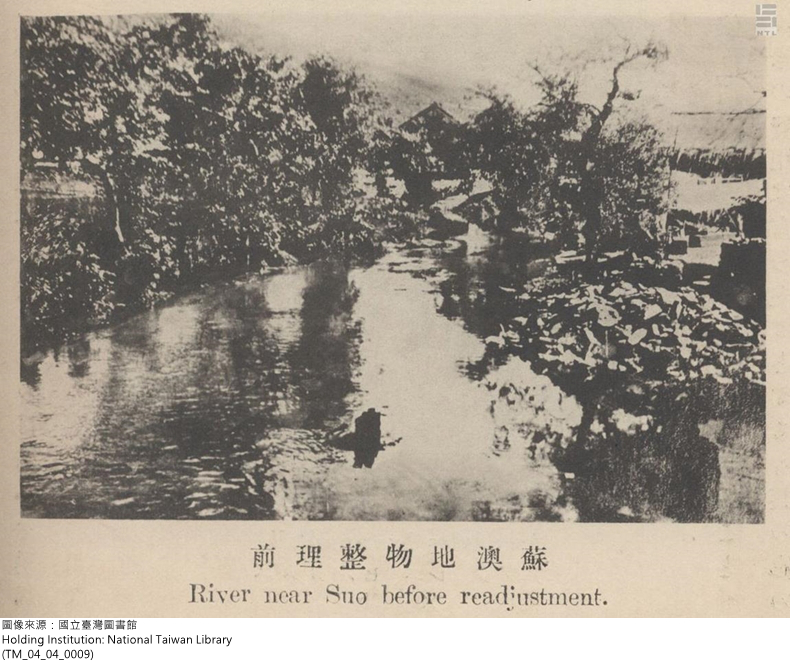

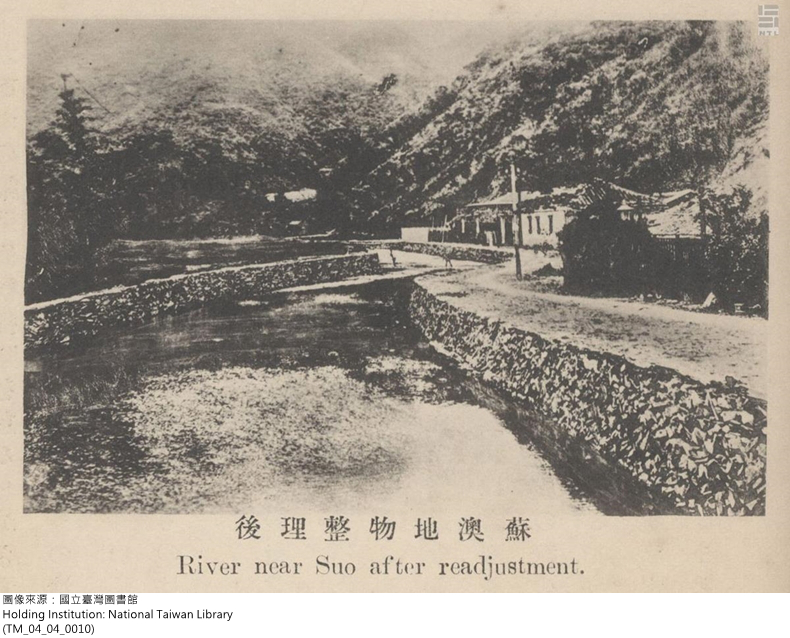

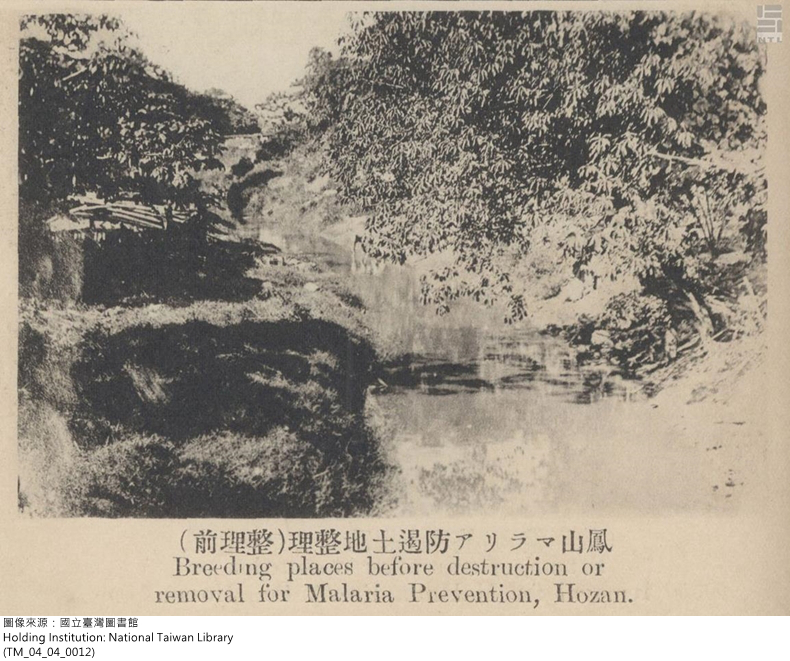

From 1900-1910, the Office of the Governor-General’s development of various industries created an outbreak of malaria cases and forced malaria prevention to the forefront of the administrations attention. In 1909, the Office of the Governor-General first attempted to stop malaria in Beitou. They started administering quinine to those who contracted malaria, as advocated by German physician Robert Koch. At the same time, Koch also encouraged the use of mosquito nets, water drainage, and grass cutting to reduce the space where malaria mosquitos could rest. The results were very positive. In 1910, the Office of the Governor-General drafted a two-pronged Malaria Extermination Initiative. The first approach was rather straight forward: in most areas drainage systems should be fixed, gutters made better, bamboo forests and weeds should be cut, etc. The second approach was rather unique: in certain areas, in addition to measures outlined in the first approach, residence would be subject to compulsory blood tests, with those found infected with the parasite required to take medication. In 1911, the Office of the Governor-General designated twelve areas for special prevention measures. Thus started their efforts in malaria prevention. In 1913, the Office of the Governor-General announced Malaria Prevention Measures, which stipulated the authority and responsibilities for prevention work, as well as correlating fines and punishments. The entire approach was human-centric, with some attention given to stopping mosquitoes. The local governments were the ones carrying out the prevention efforts, using the police and Hoko officials to enforce them. However, little success resulted from these efforts and the number of deaths from malaria continued to increase. In May 1919, the Office of the Governor-General announced new regulations to stop malaria, which included enhanced measures for dealing with mosquitos and making them the main focus. These new regulations also stipulated the establishment of Malaria Prevention Centers and needed prevention workers, as well as funding for such prevention.

Su’ao before prevention work was done

Su’ao after prevention work was done

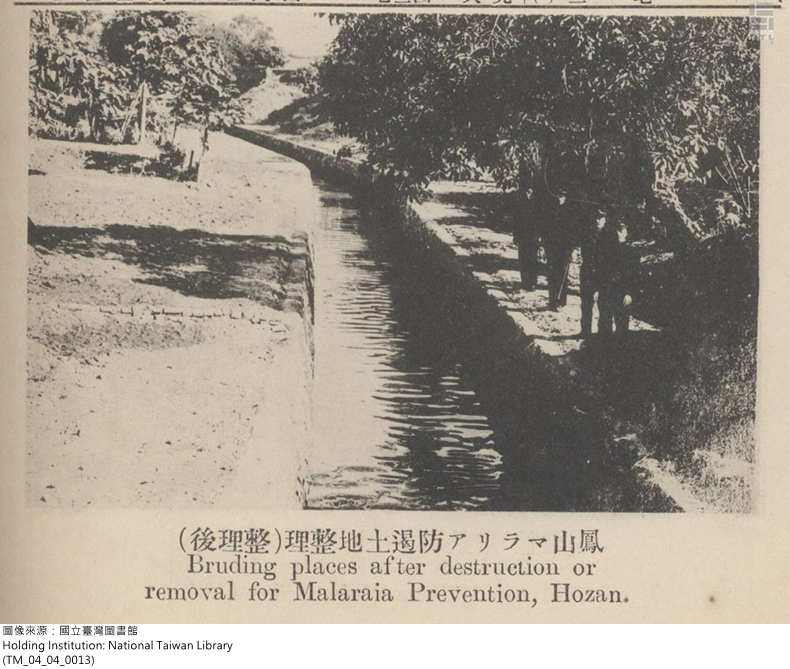

Fengshan before malaria prevention work was done

Fengshan after malaria prevention work was done

Gathering blood samples to check for the malaria parasite in Taichung

Filling in ponds where mosquito larvae grow (Changhua)

School children being checked for malaria

4.5. Taiwanese Thoughts and Reaction to Malaria Prevention

During the 1910s, the Taiwan public was caught up in the public health revolution that came in the wake of the Office of the Governor-General efforts to prevent malaria. The thoughts and reactions of the Taiwanese toward all this is worth considering. Taiwanese author Cai Qiutong, who once served as a Hoko official, published a satirical story “Winning First Place” in 1931 describing a policeman issuing an order to the Hoko official to have people mow down the bamboo and fill in holes to ward off mosquitoes. Those who did not carry the orders out were fined or even punished. In the end, this village was given first place and became the “model village for working to prevent malaria.” The policeman was also made an official for his success in the work. However, after the policeman left for his new post, the prevention efforts in the village were neglected and stopped. This story aptly showed how the officials used the Hoko system to inspect and control the people’s lives, the unreasonableness of being forced into helping with the prevention efforts—especially to have to set aside their occupations for prevention efforts without compensation, the unnecessary burdens placed on the people, and the reason why little success resulted. After the policeman left, prevention efforts in the village did not continue, which shows the difference in understanding between the officials and the people. Contrastingly, efforts directed at humans were much easier to get the public involved in. This was because of the efficacy of quinine. The public saw how symptoms were alleviated by the medicine and how there was no cost involved in treatments which meant no additional economic burden.

The Link between Mosquitos and Malaria

Taiwan author, Cai Qiu-tong

4.6. The Unique Aspects and Influence of Colonial Malaria Prevention Efforts

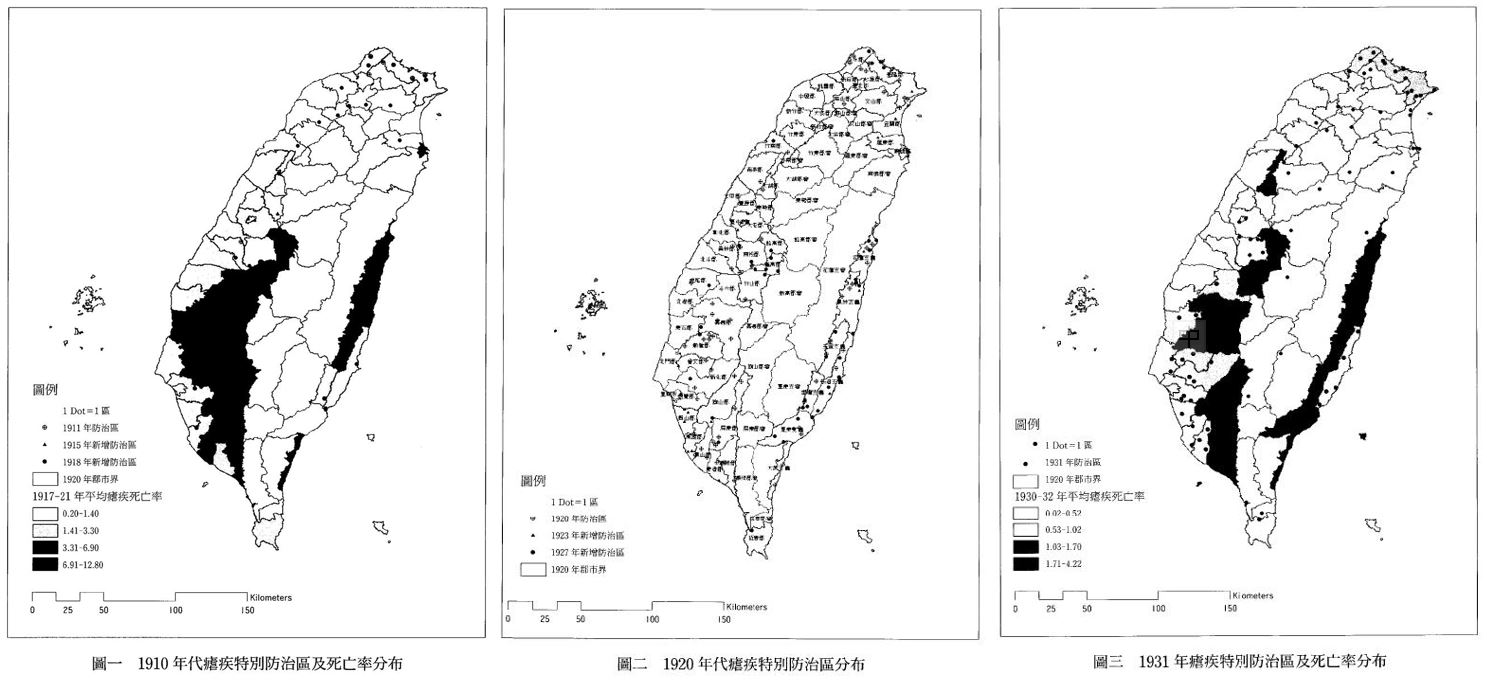

During the colonial era, the government spent years pushing prevention efforts. This, in fact, continued until the colonial period ended. From the perspective of public health, there is special historical significance and influence in these efforts. In 1911, the Office of the Governor-General started its malaria prevention initiative. In 1912, it designated 18 prevention areas. In 1924, over one hundred such areas had been designated. This number had jumped to 197 in 1944. Accompanying the gradual progress in malaria prevention was a decrease in the outbreak of malaria and deaths resulting from infection. However, considerations of budget costs stopped prevention areas from spreading all over Taiwan. In addition, on 60-70% of those living in a prevention area got their blood checked.

Sinhua Malaria prevention office

The Unique Aspects and Influence of Colonial Malaria Prevention Efforts The prevention areas designated by the government were not based on the severity of the epidemic or a high death rate, revealing the fact that the colonial government had other considerations in mind. An analysis of topography and space in Taiwan shows that in the 1910s most prevention areas were concentrated in the hilly areas. After the 1920s, the hilly areas in Taichung and Hsinchu were added, as were the valley areas in Hualian and Taitung and the plains in Chiayi and Tainan. After the 1930s, most prevention areas were concentrated in the Hualian and Taitung areas, with most being added in high mountainous regions. The change of prevention areas was based on where the Japanese were living—the cities and streets where they lived, the immigration villages in Hualian and Taitung, and areas related to government industrial development policies (such as camphor, railroads, and reservoirs). In other words, malaria prevention was carried out based on the needs of the colonial government and the economy.

Gu, Ya-wen; 2004, “Policy on the Prevention of Malaria in Taiwan during the Japanese Occupation Period—Against the People? Or against the Mosquitos?” Studies of Taiwan History, 11(2): 185-222. (TM_04_04_0019)

Nevertheless, the Japanese efforts in malaria prevention and the many insights and breakthroughs that resulted from researching the issue laid the foundation for tropical medicine research in Taiwan. The experience gained from malaria prevention during the colonial era through the workers in the prevention centers throughout Taiwan became the wellspring of experience for the development of public health on the island. Not long after the war, Taiwan experienced huge success in public health as the World Health Organization in 1965 issued a Certificate of Registration for malaria eradication to Taiwan. This success was made possible by the prevention efforts and malaria research conducted before the war.

Reference Papers

- 李尚仁,《帝國的醫師:萬巴德與英國熱帶醫學的創建》,臺北:允晨文化,2012。范燕秋,《疫病、醫學與殖民現代性:日治臺灣醫學史》,臺北:稻鄉,2010。

- 稻場紀久雄,《都市ノ醫師──濱野彌四郎ノ軌跡》,東京:水道產業新聞,1993。稻場紀久雄,《バルトン先生、明治の日本を驅ける》,東京:平凡設,2016。

- 飯島涉,《ペストと近代中囯:衛生の「制度化」と社会変容》,東京都:研文出版,2000。

- 飯島涉,《マラリアと帝國──殖民地醫學とアジアの広域秩序》,東京:東京大學,2005。

- 范燕秋,〈鼠疫與臺灣之公共衛生(1896-1917)〉,《臺灣分館館刊》1(3):1995,頁59-84。

- 范燕秋,〈醫學與殖民擴張──以日治時期臺灣瘧疾研究為例〉,《新史學》7(3):1996,頁133-173。

- 范燕秋,〈新醫學在臺灣的實踐(1898-1906)──從後藤新平《國家衛生原理》談起〉,收錄於李尚仁主編《帝國與現代醫學》,臺北:聯經,2008,頁19-53。

- 張隆志,〈後藤新平:生物學政治與臺灣殖民現代性的構築(1898-1906)〉,《二十世紀臺灣歷史與人物學術研討會》,臺北:國史館主辦,2001,頁1235-1260。飯島涉,〈コレラ流行與東亞的防疫系統──香港、上海、橫濱〉《橫浜與上海近代都市形成史比較研究》,橫濱:橫濱開港資料普及協會,1995。

- 顧雅文,〈日治時期臺灣的金雞納樹栽培與奎寧製藥〉,《臺灣史研究》18(3),2011.9:,頁7-91。

- 顧雅文,〈日治時期臺灣瘧疾防遏政策──對人法?對蚊法?〉,《臺灣史研究》11(2),2004.12,頁185-222。

- 呂哲奇,〈日治時期台灣衛生工程顧問爸爾登(William Kinninmond Burton)對於臺灣城市近代化影響之研究〉,中壢:中原大學建築系碩士論文,1999年。